Unidentified artist

Unidentified artistJohn Freake, about 1671 and 1674

Description

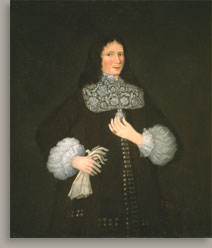

John Freake is a three-quarter-length portrait of a man turned slightly to the right. His dark brown hair is parted in the center and falls on his shoulders. He has dark brown eyebrows, brown eyes, and a narrow moustache of the same color. His flesh tones are predominantly pink with deeper red on the cheeks and lips. The face is drawn as an oval with a pointed chin. The nose is straight and narrow.

The figure stands perfectly erect with both arms bent at different angles so that the hands are presented in front of the body at different heights. The proper left hand rests at the center of the chest with the fingers turned up and touching a tassel. The proper right hand is held at hip level and holds a pair of gloves. The extended fingers of the right hand have become transparent over time, suggesting that the artist represented them folded under to grasp the gloves before changing them to their current position. The variation in hand placement—higher/lower, centered/off center—results in the right elbow projecting out from the body and the left elbow held closer in, lending an interesting asymmetry to the composition.

The figure is dressed in a dark brown coat that flares out at the sides. The sleeves of the coat end halfway down the forearm, revealing voluminous white tufted sleeves with ruffled cuffs. The coat is ornamented with twenty-two silver buttons in front, more of which are covered by the left hand; others are unseen because the coat is truncated by the bottom edge of the composition. Each buttonhole is outlined with silver thread. Only the top seven buttons are fastened. In addition, two groups of four buttons each run horizontally at different heights on the proper right side of the coat, presumably to secure pockets. The pocket closest to the front closure is lower than the outer one. The figure wears a white lace collar that lies flat across the chest and turns up in a gentle arc at the neck to frame the jawline. The collar roughly forms a rectangle with rounded corners. The dark brown of the coat shows through the negative spaces of the lace, which features vines wrapping around circular flowers. The pattern is mirrored either side of the closure. The man wears a gold-framed oval pin at the throat, a white ornament at the base of the lace collar, and a gold signet ring on the little finger of the proper left hand. The background is an even tone of dark brown, just a shade lighter than the coat.

Biography

John Freake was born in 1631 and baptized on July 3 at the manor house Hinton St. Mary, Dorset County, England (fig. 1).1 He was the third child of Thomas (1598–1642) and Mary Dodington Freke (d. 1686), a landed family of Hinton.2 John's grandfather was Sir Thomas Freke (1563–1633), who was knighted by James I, served twice as a member of Parliament for Dorset, and for thirty years was a deputy lieutenant of the county of Dorset.3 In 1610 Sir Thomas paid to build the parish church at Shroton, also called Iwerne Courtney, Dorset County, where he was later buried under the family coat of arms.4 John Freake's grandfather also participated in colonial ventures as a member of the king's Council for Virginia (1607) and the council for the Virginia Company (1612).5 A portrait of Sir Thomas Freke remains in the family, and portraits of John Freake's uncles, Raufe Freke (1596–1683/4) and William Freke (1605–1656), hang in the Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

John emigrated from England by 1658 and became a successful merchant and attorney in Boston.6 His family background suggests that he brought significant financial and other resources with him from England. John married Elizabeth Clarke (1642–1713) in Boston on May 28, 1661.7 The couple settled in Boston's North End, and between 1662 and 1674 they had eight children.8 John Freake held public office in his adopted city as a juryman and a constable and also served as a trustee of the Second Church (Puritan) of Boston.9

![]()

Figure 1. Photograph of John Freake’s birthplace, Hinton St. Mary Manor House, Dorset, England. © Crown copyright NMR.

Shortly after his arrival from England Freake became a business associate of Captain Samuel Scarlett (d. 1675).10 In 1669 Freake and Scarlett jointly purchased waterfront property at the "Sea or Harbor of Boston", including "the Ware-Houses Edifices, buildings shops Sellers, rent & Rents" belonging to it.11 In 1671/2 Freake and his partner were granted permission to maintain a wharf in front of their property for twenty years, and they were to be compensated by the city five shillings per year for maintaining the causeway.12 Their joint business holdings eventually included a dock, wharf, warehouses, dwelling houses, and a barge.13

John Freake was a man who pushed boundaries. In 1666 he supported recognition of King Charles's commissioners in Boston, a direct challenge to the authority of the Puritan government of the colony.14 He signed a petition in 1673 to have letters of reprisal issued after seven armed merchant ships were lost during the third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674).15 Because of his and other merchants' opposition to local authority in 1666, the General Court denied their request.16 Despite the continuing risks of attack by Dutch ships, Freake traded in Acadia (Maine) in the waning years of the third Anglo-Dutch War.

Recognizing the danger to his livelihood, Freake tested the political resolve of the colony late in 1674 by sending his bark Philip to Maine on a trading voyage. The Philip was seized at anchor near Mount Desert by a Dutch privateer, and Freake petitioned the General Court to recover the lost vessel.17 This time the colonial government supported Freake by commissioning Capt. Samuel Moseley, who would soon earn a reputation for daring as a privateer and soldier during King Philip's War, to retrieve Freake's bark.18 Moseley apprehended those responsible for capturing the Philip and they were charged in Boston for "pyrattically and felloniously seize[ing] & take[ing] seuerall smale vessells," including "the barcque Phillip & her Goods" and "wounding" the ship's master and mate.19

On May 4, 1675, before the trial of the Dutch privateers took place, John Freake died accidentally on board another one of his ships that had just arrived from Virginia. The diarist Samuel Sewall (1652–1730) recorded the accident: "Tuesday, May 4 Cpt Scarlet, Mr. Smith, Mr. Freak killed by a blow of powder on Ship board. Mr. Freak killed outright."20 Rev. Simon Bradstreet expanded upon Sewall's version of the accident: "Mr. Freak and Capt. Scarlett of Boston were killed by ye blowing up of ye deck of a ship by ye Carelessness of some aboard. There were diverse others that wr very dangerously wounded and some of yem after dyed."21 Scarlett lived long enough to prepare a will, in which he named John Freake, Jr., as a beneficiary. Scarlett also left annual gifts to the Second Church, Harvard College, and for the relief of the poor in his native town Kersey, Suffolk County, England.22 John Freake's probate inventory lists real and personal property worth nearly two thousand four hundred pounds, a substantial estate for the late seventeenth century. His holdings included partial ownership of six ships valued at a total of six hundred and one pounds; half interest of the land, houses, wharf, and dock owned presumably with Samuel Scarlett at four hundred fifty pounds; one eighth of the "millnes in Boston" at four hundred pounds; the Freakes' "dwelling house ould & new with ye land" four hundred fifty pounds; one-fifth of a brew house and land at Fort Hill at one hundred fifty pounds; silver plate at sixty-eight pounds; and a servant or slave listed as "One Negroe named Coffee" at thrity pounds.23 Freake was buried in the Granary Burying Ground in Boston, and his tomb bears a coat of arms that combines the Freake family arms used in Shroton, County Dorset, England, with the Clarke coat of arms for his wife, Elizabeth.24

Analysis

John Freake is one of about ten portraits that were painted by the same artist in Boston between 1670 and 1674. The paintings are done in a style that originated in Elizabethan England and remained in use there throughout the third quarter of the seventeenth century, although it had been replaced at court and among fashionable sitters by the baroque style which Anthony Van Dyck (1599–1641) introduced to England in the 1630s.25 The Elizabethan style emphasized linear attention to the contours of figures and costume details, rather than the baroque's use of light and shadow to create a believable illusion of volume and space. This composition is organized on a strong vertical axis, which the artist established with the standing figure and reinforced by the line of silver buttons down the front of the coat. That vertical line is accented by the diagonal lines created by John Freake's bent arms, the round forms of his voluminous sleeves, and the swirling pattern of his lace collar. Even the buttons are not perfectly vertical but rather form a slight angle that bends where the coat is unbuttoned. Because of the portrait's stylistic relationship to British painting, it seems likely that the artist who painted this canvas received some training either in England or in the studio of an emigrant artist who learned there.

|

|

| Figure 2. Unidentified artist, seventeenth century, American, Elizabeth Clarke Freake (Mrs. John Freake) and Baby Mary, probably painted in 1671 and updated in 1674, oil on canvas, 42 1/2 x 36 3/4 in. (108 x 93.3 cm), Worcester Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Albert W. Rice, 1963.134. |

|

|

|

| Figure 3. X-Ray of John Freake, taken by Philip Klausmeyer, 2000. |

The date proposed for John Freake, about 1671 and 1674, is based on the interpretation of inscriptions on the companion portrait. The inscription at the bottom right of Elizabeth Clarke Freake (Mrs. John Freake) and Baby Mary gives the sitter's age as 29 and the date 167[1]; the one at the center left notes the age of the child as six months. Radiography reveals that the portrait of the child was added. Given that Mary Freake was born May 6, 1674, that addition and other changes likely occurred in November or early December 1674. John's portrait was most likely painted and revised at the same time.

Radiography shows that John Freake underwent changes, too. Alan Burroughs of the Fogg Art Museum examined the surface with X-ray in 1934 in preparation for the first scholarly study and exhibition of seventeenth-century American paintings. That exhibition was held at the Worcester Art Museum. Burroughs concluded that John Freake's eyes were raised three-eighths of an inch, demonstrating "the painter's sensitiveness to details of drawing, design, and reality of pose."26 That first X-ray study of the portrait was apparently limited to the area representing the sitter's head.

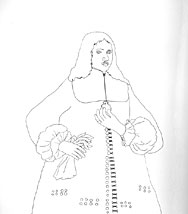

In 1981 the entire portrait was studied with X-ray (fig. 3) by Worcester's conservators Norman Muller and David Findley in preparation for the most comprehensive exhibition to date of seventeenth-century American art and material culture. That exhibition was organized by Jonathan Fairbanks at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The new X-ray findings were interpreted by Susan Strickler, then curator of the American collection at Worcester, who argued that John Freake's eyes were lowered, not raised, and that his face was broadened (fig. 4).27 Strickler also proposed that Freake's hair may have been moved forward onto his shoulders, his hairline elevated on his forehead, and his collar moved down and its pattern redefined. Such relatively minor adjustments may have been made in the course of the original sittings about 1671. More substantial changes were made to the hands, however, likely about 1674, when Elizabeth Freake's portrait is thought to have been dramatically altered (fig. 5). Originally John held a glove in each hand, Strickler argued, but the one in the proper left hand was moved to the right hand. The left hand was turned up slightly to cradle the ornament below the collar. The rotation of that hand allowed for the addition of Freake's signet ring his little finger and more buttons in the section of the coat previously blocked by the hanging portion of the glove in his left hand. Technical analysis conducted by paintings conservator Philip Klausmeyer for this catalogue indicates that in the original composition Freake used both hands to hold a single glove.

|

|

||

| Figure 4. Line drawing of the composition of John Freake as it is thought to have appeared about 1671. Drawing by David Findlay. | Figure 5. Line drawing of the final composition, about 1674. Drawing by David Findlay. |

Freake is represented as a member of the emerging mercantile elite in Puritan Boston. His hair, clothing, and demeanor all contribute to that identity. While some contemporary ministers preached anxiously about the sin of vanity and warned parishioners about paying too much attention to worldly goods at the expense of their eternal soul, men like Freake apparently did not see a conflict between their financial success and their spiritual lives. Indeed, Freake was active as a trustee of the Second Church of Boston and probably saw his outward prosperity as a sign of God's approval of his success and that of the thriving colony.29

The sitter's hair and moustache add to the image of a stylish merchant.30 His shoulder-length hair would have been impractical for an artisan or laborer, but Freake was also careful to avoid wearing a wig. Although worn by a handful of men in Boston, wigs were still suspected of hinting at self-absorption and even immorality. Instead, his hair was carefully styled in keeping with his upper-middling status.

The dark-brown coat worn by Freake is of the Cassack or Persian style popular in London among wealthy merchants and aristocrats in the 1660s and 1670s and further signifies his elevated status.31 The coat is decorated with more than thirty-eight silver buttons, crafted of an expensive material and numbering many more than necessary to protect its wearer from the cold. The coat is further ornamented with silver embroidery encircling the buttonholes. The list of John Freake's personal effects upon his death includes "his owne wearing apparrell silke linnen and woollen" valued at fifteen pounds. The inventory also includes "a remnant searge and black cloath" at one pound ten shillings, perhaps the same woolen from which his coat had been made.32 It would appear that the artist was expected to carefully describe the sitter's actual possessions in a portrait such as John Freake's.

One of the focal points of the painting is the flat lace collar that represents a field of swirling vines encircling flowers. This lace has long been described by art historians as a Spanish version of Venetian lace possibly imported from Venice, Spain, or Flanders.33 The lace is not only a decorative accent to the portrait, but also a sign of Freake's position as a merchant capable of affording imported luxuries. Freake directs the viewer's attention to the collar with his touch to the ornament, probably a tassel, directly below.34

On the hand that touches the tassel, Freake wears a gold signet ring on his little finger. The ring is the only gold item in the portrait and stands out further by its placement near the center of the composition. Because they were engraved with the family coat of arms and made of precious metal, signet rings were important emblems of prominent families and were passed as heirlooms from father to son.35 Freake's inventory records his owne signet and sett of gould Buttons valued at three pounds, reinforcing the argument that the portrait describes significant elements of the sitter's actual wardrobe.36

The gloves that Freake holds in his proper right hand are another sign of his gentility.37 At the time of his death, Freake owned "10 paire of Gloves" worth seven shillings.38 The importance of gloves in seventeenth-century culture is demonstrated by their inclusion in contemporary portraits: the English portrait, John Winthrop (1640, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts), and two works probably painted by the same hand as John Freake, Edward Rawson (1670, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston) and Robert Gibbs (1670, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)—portraits of Freake's peer and a child, respectively. Further underscoring the significance of gloves in early America, they were given as funerary and wedding gifts to honored friends.39

In short, John Freake is among the last portraits in England or America in the Elizabethan style, which originated to honor the power and wealth of a monarch and her court. It is also among the first paintings that survive from New England and one of perhaps two dozen seventeenth-century Anglo-American portraits. John Freake also stands out as one of the few portraits of a seventeenth-century gentleman that does not depict either a clergyman or a man in military costume. As a representative of the shifting center of power from the Puritan theocracy to the economic elite in Boston, it provides an important foundation for the hundreds of representations of mercantile sitters that would be commissioned in the eighteenth century.

Notes

1. Freke 1825, 5, lists "John [Freake], born at Hinton, 1631, and married to Elizabeth Clarke, New England." Hutchins 1973, IV, 86, gives the date of his baptism.

2. Freke 1825, 5.

3. Fry 1935, 26.

4. Dorset Monuments, III, part 1, 1970, 126, 127, 548.

5. Hasler 1981, II, 158.

6. The earliest known mention of John Freake in Boston is his signature on a probate inventory, June 30, 1658, in NEHGR 9 (October 1855): 344.

7. NEHGR 19 (April 1865): 169.

8. Boston Births 1883, 84, 88, 100, 104, 110, 114, 123, 132.

9. Court of Assistants 1901, 2; Boston Records 1881b, 66; and Suffolk County Deeds, VII, 117.

10. Freake and Scarlett prepared a probate inventory in Boston, June 30, 1658, noted in NEHGR, 9 (October 1855): 344. See also 1661, Suffolk County Deeds, IV, 88.

11. Suffolk County Deeds, VI, 150–54.

12. Boston Records 1881b, 64–65.

13. Covenant between Elizabeth Freake and John Scarlett, March 9, 1676/7, Suffolk County Deeds, XXX, 49.

14. Bolton 1919, II, 389, and Craven 1986, 40.

15. Petition, October 24, 1673, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, LXI, 11.

16. Bailyn 1955, 131.

17. George Manning, captain of the Philip, to John Freake, December 27, 1674, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, LXI, 65, and Petition, February 15, 1674/5, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, LXI, 66; and Bodge 1910, 44–54.

18. Massachusetts Archives, Boston, LXI, 79; and NEHGR 37 (April 1883): 170–73.

19. Court of Assistants 1901, 37.

20. Sewall 1973, I, 12. Judy Graham suggested Sewall's diary as a source for biographical information on the Freakes.

21. "Bradstreet's Journal," NEHGR 8 (October 1854): 329.

22. Samuel Scarlett, Will, April 22, 1675, Suffolk County Probate, Boston.

23. "Probate inventory of the estate of John Freake," 24th day, 7th month, 1675, Suffolk County, miscellaneous docket, V, 294–96.

24. Bolton 1919, II, 389, 390.

25. Craven 1986, 48–51.

26. Burroughs 1936, 11.

27. Strickler 1981–1982, 53–54.

28. Fairbanks 1982, III, 461–62.

29. For Freake's church involvement, Suffolk County Deeds, VII, 117; Craven 1986, 14, 43, 106.

30. Craven 1986, 42–43; Sherman 1990–1991, 37; and Craven 1993, 106–7. John Freake's hair has also been described as an early type of periwig, but that is not consistent with the appearance of the portrait. Warwick and Pitz 1929, 123.

31. Craven 1986, 43; Sherman, 1990–1991, 36, 37.

32. "Probate inventory of the estate of John Freake," 24th day, 7th month, 1675, Suffolk County, miscellaneous docket, V, 295. Strickler 1981–1982, 54, reads the last word incorrectly as "coate." John Freake's coat has also been described as velvet (Craven 1986, 43) and "cut velvet" (Craven 1993, 106).

33. Morris 1927, 7; Craven 1986, 43; Sherman 1990–1991, 36, 37; Craven 1993, 106.

34. Craven 1986, 43, interprets it as "an ornate silver brooch." Since the surface is represented like the lace rather than the buttons, the ornament is likely made of threads rather than metal.

35. For surviving rings, including one inset with a carnelian and owned by John Freake's contemporary John Leverett (1616–1679), see Fales 1995, 19, 20.

36. "Probate inventory of the estate of John Freake," 24th day, 7th month, 1675, Suffolk County, miscellaneous docket, V, 295.

37. Craven 1993, 106.

38. Probate inventory of the estate of John Freake, 24th day, 7th month, 1675, Suffolk County, miscellaneous docket, V, 295.

39. For gloves given at funerals, see Sewall 1973, I, 87; II, 866; and at a wedding, I, 454.