Gilbert Stuart Gilbert Stuart

Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton

(Mrs. Perez Morton), 1802–20

Description

Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton) is a slightly larger-than-half-length view of a standing woman turned slightly to the viewer’s left. Although the face is the most finished part of this portrait, Morton’s individual features are not crisply defined. Her pale red lips are somewhat blurry, and the bottom lip is almost indistinguishable from the top. The strands of brown hair that escape the sheer veil and curl loosely over her forehead were painted before Stuart added the creamy paint to her forehead. One ringlet hangs over the corner of her proper left eye; another over the eyebrow. What appears to be the top of a bun is visible through the sketchy brown lines that define the veil.

Morton’s dark brown eyes gaze directly at the viewer. Stuart did not paint her pupils as distinct from her irises, and it is difficult to spot them. The area of the eye outside the iris is flesh colored and not white. A tiny pinhead-size dot of white highlights the pupil area in her proper left eye; another accents the right corner of her proper right eye. Her top eyelids are defined with two curving brown lines, but the lower lid is only partly rimmed on the proper left eye, and the outline is irregular on the proper right eye. Her eyebrows are dark and cursorily painted.

A large hoop earring with light blue strokes and a few opaque yellow highlights to suggest stones and gold embellishes her visible ear. Her cheeks, chin, and nose are pink, in contrast to her pale forehead. Morton’s nose, highlighted with a broken line of white paint, is slender. The shadows cast to the lower left of her nose, under her chin, and beneath the strand of pearls at her neck suggest a light source in the upper right of the painting.

Stuart painted Morton with both arms raised, as if adjusting the sheer veil that covers her head, but this spontaneous gesture was not his first intention. The thin application of paint does not completely conceal Stuart’s initial underlying pose, in which the sitter’s proper left arm crossed over her stomach and rested on top of her proper right wrist. In the present pose it is impossible to know whether Morton is lifting the veil from her face or lowering it. Stuart’s quickly sketched dark broken lines to indicate multiple folds in the veil’s sheer fabric and to suggest movement, especially where the veil covers her hands. To suggest the fabric’s transparency, Stuart painted the veil using varying shades of gray over part of the proper left side of Morton’s face. The length of the veil is not clear, but a dark rectangular outline under her left arm suggests its bottom.

Stuart blocked in Morton’s proper right arm with white paint and further defined it with a loose black outline on its underside, brown strokes on either side of the forearm, and jagged strokes of brown near the shoulder. The elbow of her proper right arm is bent at almost a ninety-degree angle. A thick, dark black outline runs along her waist and down her right side. Her proper left arm is bent and raised higher than her right. Sketchy strokes of black paint define the contours of her proper left side, shoulder, and arm. Both hands disappear into the veil.

Morton is wearing a high-waisted, long-sleeved white dress, which is very broadly painted. Large, rough strokes of white paint were thickly applied on top of a dark rectangular area extending from the neckline of the dress to just below the bustline on the right side. This dark area now appears as a light gray-blue. Back-and-forth brushstrokes suggest the artist was trying to cover the area. On Morton’s dress, light gray-blue paint appears at the neckline and across her stomach below her proper left arm from the previous pose. There are also spots of thicker yellow paint to the left and right of the light gray-blue rectangular area on the white dress. After the veil and dress were blocked in with whites and grays, Stuart added definition with sketchy, dark lines, as seen by the thick, black brushstroke over Morton’s left wrist.

The change in composition from crossed to raised arms distorted Morton’s body so that her top half appears twisted to the left, creating and awkward bustline, but the artist did not correct it. The neckline of Morton’s dress is not clearly defined, and only a small expanse of pale flesh is visible. The sheer ruffles or lace from her shift, visible along the neckline of the dress, were painted quickly and with a slight impasto. Thick white paint covers the top right side of the neckline, hiding some of the ruffles. A short strand of graduated pearls falls just below her collarbone, but it does not appear to completely circle her neck.

The boldly painted upper background seems to suggest blue sky and cream-colored clouds tinged with orange. Darker gray clouds occupy the top left corner. The background below Morton’s proper right arm is murky, but not as gray as the area below her raised proper left arm. It is difficult to determine whether the background of the painting or the fabric of the veil extends over the upper part of her proper right arm and shoulder, because Stuart did not define the contour line as he did on the underside of her arm. Instead, he loosely brushed gray and brown paint over the white of her proper right shoulder and arm. Where the veil obscures the hand on her raised proper right arm, there is a smattering of red and yellow paint on the dark background, and the canvas weave is visible.

Biography

Sarah Wentworth Morton was a poet whose published work of the 1790s received the praise of her contemporaries, who called her "the American Sappho" after the Greek lyric poetess.1 Baptized Sarah Apthorp at King’s Chapel in Boston on August 29, 1759, she was the third of ten children born to the merchant James Apthorp (1731–1799) and Sarah Wentworth (1735–1820).2 James Apthorp lived at 74 King (later State) Street until about 1768, when he moved his family to the Braintree, where he had inherited property. In Braintree, the Apthorps attended the Episcopal Christ Church, which was associated with Loyalists at the beginning of the Revolution. Town records of June 1777 list Apthorp among persons suspected of being "inimical" to the colonial cause.3 Sarah’s mother was the daughter of the Boston merchant Samuel Wentworth (1708–1766) and the granddaughter of Lieutenant-Governor John Wentworth (1671–1730), of Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Sarah had great pride in both her Wentworth and Apthorp ancestors, and at some point after her marriage to Perez Morton (1750–1837) she added her mother’s maiden name to her married name.4

Sarah Apthorp and Perez Morton were married at Trinity Church, Boston, on February 24, 1781.5 Perez Morton was the son of Joseph Morton (1712–1793), the proprietor of the White Horse Tavern in Boston, and his first wife, Anna Bullock (d. 1759). After graduating from Harvard in 1771, Perez Morton studied law and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar as an attorney on July 27, 1774. During the Revolution he practiced law and was a leading member of the Committee of Safety and the Committee of Correspondence. He was also an active Mason, and in April 1776 he won acclaim for his delivery of the funeral address for General Joseph Warren, a fellow Mason who had been killed during the Battle of Bunker Hill. In 1778 Perez Morton served as major and aide-de-camp to General Hancock in the Continental Army.6 The following year he was appointed attorney for Suffolk County.7

Shortly after their marriage, the Mortons resided in the brick house in Boston where Sarah had lived until her family moved to Braintree.8 Sarah and Perez had four daughters and one son, who were all baptized at Trinity Church in Boston. Sarah Apthorp Morton (1782–1844), Anna Louisa Morton (1783–1843), Frances Wentworth Morton (1785–1831), and Charlotte Morton (1787–1819) lived to adulthood, but only Sarah and Charlotte married. Charles Ward Apthorp Morton was born on August 15, 1786, and died on February 28, 1809. An infant son born in April 1789, whose baptism was not recorded at Trinity Church, lived only eighteen hours.9

The Mortons were members of a prominent social circle. Along with the James Swans, Harrison Gray Otises, Isaac Winslows, and others, the Mortons formed a club in the winter of 1784–85 for playing cards and dancing. Although bets were limited to twenty-five cents, the group’s activities were criticized in the newspaper. The club was deemed "an Assembly so totally repugnant to virtue, as in its very name (Sans Souci, or free and easy )," and encouraged to disband.10 Later, the club was satirized in a play, Sans Souci, alias, Free and Easy:–Or, an Evening’s Peep in a Polite Circle. An entirely new entertainment in three Acts, printed in late January 1785. The Mortons, who were identified as Mr. and Madam Importance, were portrayed as pompous, snobbish, and exclusive.11

A more serious public scandal involving the Mortons, publicized in the Boston newspapers in the summer of 1788, undoubtedly caused Sarah Wentworth Morton great pain. About two years earlier, Sarah’s younger sister Frances "Fanny" Theodora Apthorp (1766–1788) had come to live with the Mortons in Boston. Fanny had an affair with Perez Morton and at the end of 1787 gave birth to a daughter. Fanny’s diary and letters from August 1788 include instructions to Perez Morton to take care of her child "for you know in the sight of heaven you are the Father of it." The day before she committed suicide on August 28, 1788, instead of publicly confronting Perez Morton as her father had requested, Fanny left a note begging forgiveness from her family, especially her sister.12 Although Perez Morton was implicated by a jury in Fanny’s suicide, his friends John Adams (1735–1826) and James Bowdoin (1726–1790) defended him in the Massachusetts Centinel on October 7, 1788:

We are happy in being able to announce to the publick, that the accusations brought against a fellow citizen, in consequence of a late unhappy event, and which have been the cause of so much domestick calamity, and publick speculation, have, at the mutual desire of the parties, been submitted to, and fully inquired into by their Excellencies JAMES BOWDOIN, and JOHN ADAMS, Esq’rs, and that the result of their inquiry is, that the said accusations "are not, in any degree, supported, and that therefore there is just ground for the restoration of peace and harmony between them [likely Perez Morton and James Apthorp, the father of Sarah and Fanny]," and in consequence thereof, they have recommended to them, with the spirit of candour and mutual condescension, again to embrace in friendship and affection.

We would add, that were it not for the verdict of the jury of inquest to the contrary (for verdicts must always be respected) it would have been the wish of many, that the extraordinary conduct of the deceased, had been early attributed to the only accountable cause, an insane state of mind.13

The scandal was so well known that there was no need for Bowdoin and Adams to identify Perez Morton by name. Criticism of their defense and disregard of the jury’s findings appeared in the Herald of Freedom and the Federal Advertiser.14 The scandal gained strength with the announcement of the publication of the first American novel, The Power of Sympathy Or, the Triumph of Nature, in January 1789.15 Although the novel was set in Rhode Island, its plot was clearly the story of Frances Apthorp and Perez Morton, whose name was only weakly disguised as Mr. Martin.16

The affair apparently had no ill effect on Perez Morton’s career, and Sarah remained married to him. Perez Morton, as a Democratic-Repubican, was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in May 1794. After he and Sarah moved to Dorchester, Perez was elected to the House of Representatives again in 1803 and in 1806 was elected speaker. He was appointed attorney general in 1811 and held the office for twenty years.17

Soon after the scandal, Sarah Wentworth Morton’s first published poem, "Invocation to Hope," appeared in the July 1789 issue of the recently established Massachusetts Magazine under the pseudonym "Constantina." She later wrote under the pseudonyms "Philenia" or "Philenia Constantina."18 Besides her neoclassical poems, which often used heroic couplets and ballad stanzas, she also wrote hymns and sonnets. Her subject matter was both personal and public and often patriotic, celebrating the new nation, its ideals, and its leaders. Her work also reflected a woman with definitive opinions about many of the period’s topical issues, including the plight of Native Americans. Her first long poem, Ouâbi or the Virtues of Nature, An Indian Tale. In Four Cantos, published in December 1790, was even reviewed in London, where it inspired a three-act play.19 Morton’s abolitionist views surface in a few poems, including "The African Chief," which appeared in the June 9, 1792, issue of the Columbian Centinel and described a slave’s decision to die to escape a slave ship.20 Her 1794 poems "Marie Antoinette" and "Bativia" reveal that she did not share her husband’s pro-French sentiments.21 Morton’s verses continued to appear regularly in the Massachusetts Magazine’s "Seat of the Muses" column through 1793 as well as in the Boston Columbian Centinel until 1794. They were also reprinted in Philadelphia, New York, and New Hampshire journals. After the turn of the century, her poems appeared occasionally in the Monthly Anthology and Boston Review until 1807.22

In the introduction to her "Beacon Hill: A Local Poem, Historic and Descriptive," Morton defended her "application to literature." "It is only amid the leisure and retirement, to which the sultry season is devoted," she wrote,

that I permit myself to hold converse with the Muses; nor does their enchantment ever allure me from one personal occupation, which my station renders bligatory; but those hours, which might otherwise be lost in dissipation, or sunk in languor, are alone resigned to the unoffending charms of Poetry and Science.23

"Beacon Hill" was published in 1797 as the first part of an ambitious larger work. "The apprehensive feelings of the author," Morton explained, "did not permit her at present to offer more than the first book."24 The poem, dedicated to the Revolutionary soldiers who fought under George Washington, looks at the end of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the siege of Boston, and the Declaration of Independence and pays tribute to Washington and the Revolutionary leaders in each colony. William Bentley (1759–1819), pastor at Salem’s Second Congregational Church, wrote in his diary in November 1797, "The talk now about Mrs. Morton’s Poem, Beacon Hill, & it is said to exceed any poetic composition from a female pen. She is called the American Sappho. Mr. Paine calls her so. Besides Mr. Stearns is soon to publish The Lady’s Philosophy of Love, which they have begun to praise before they have seen it." Bentley also voiced his doubts about the quality of the poetry of the time, and it does not appear that Morton was encouraged to complete the other installments of "Beacon Hill," which were never published.25

In 1823 Morton published a compilation of prose and poems in My Mind And Its Thoughts, in Sketches, Fragments, and Essays. It was the first work to which she signed her own name. In addition to new poems written to celebrate national and local events, the volume contained careful revisions of poems that had been published earlier in newspapers or journals under her pseudonyms. The book’s essays encompassed such varied topics as marriage, physiognomy, the sexes, civility, and age. As she noted in the introduction, "Thus occupied—with neither leisure, nor disposition, nor capacity to write a Book, there has always been opportunity to pen a thought, or to pencil a recollection."26 A list of subscribers at the end of the volume is topped by "JOHN ADAMS, late President of the United States" and "His Excellency JOHN BROOKS, Governor of Massachusetts." In total, 34 women and 125 men ordered copies of the book in advance of its publication.27 Many of the verses, such as "Stanzas To A Recently United Husband" or "Lamentations Of An Unfortunate Mother, Over The Tomb Of Her Only Son," are extremely personal and sad.28 Her "Apology" at the end of the text suggests that writing brought her consolation from the many disappointments and grief she experienced in her life.29

That Morton was devoted to literature is hardly surprising, given her penchant for writing. In November 1792 Morton was one of the founders of the Boston Library Society.30 The ledgers of the society attest to the numerous books she read, and an inventory of her estate contains more than 250 books, including 20 volumes of Shakespeare and 9 volumes of Pope.31 Her literary interests also extended to the theater. Both she and her husband were involved in repealing the 1750 colonial law entitled "An Act to prevent Stage Plays, and other Theatrical Entertainments," and Perez Morton was a trustee and shareholder of the resulting Federal Street Theatre.32

Perez Morton died in Dorchester on October 14, 1837, and left all his real and personal estate to "my beloved wife Sarah Wentworth Morton."33 After his death, Sarah moved from Dorcester to the Braintree house, where she had lived as a child, then within the township of Quincy.34 She died on May 14, 1846, and funeral services were held at Christ Church in Quincy on Saturday, May 16. By the time of her death, her fame as a poet had long since been forgotten; none of her obituaries in the Quincy Patriot, Boston Daily Mail, or Daily Evening Transcript made any mention of her literary career, noting simply that she was the widow of the late Honorable Perez Morton.35 Her will instructed that she be interred in the Apthorp family vault in King’s Chapel. She also requested that the remains of her daughter Frances Wentworth and her son, Charles, be reinterred in the family vault so that she would have her "own remains between those of my two dearly beloved and lamented children."36

Analysis

In 1902 John Morton Clinch wrote to the Worcester Art Museum about his family’s surprise discovery:

At the late exhibition of Fair Women at Copley Hall, there was a portrait of Mrs. Perez Morton by Stuart, loaned by your Museum. Mrs. Morton was my Great-Grandmother and I was much surprised to see this portrait, as we had never seen or heard of it before: I should therefore be much pleased if you could give me any account of it’s history before it came into the possession of the Museum. The other portrait of Mrs. Morton exhibited belongs in our family, and is considered one of Stuart’s finest works; we also have a copy of this on panel made by Stuart for an admirer of Mrs. Morton, and these two portraits being the only ones of Mrs. Morton of which we had any knowledge. I would greatly desire at some future time, to have a copy made of your portrait if the Trustees of the Museum would give their consent.37

|

|

|

|

|

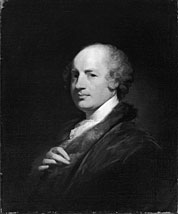

Figure 1. Gilbert Stuart, Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp), about 1802, oil on panel, 29 1/2 x 24 in. (74.9 x 61 cm), Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware. |

|

Figure 2. Gilbert Stuart, Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp), about 1802, oil on canvas, 29 1/8 x 24 in. (74 x 61 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Juliana Cheney Edwards Collection, Bequest of Grace Edwards in Memory of her mother, 39.681. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. © 2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved. |

The two other Stuart portraits of Morton that Clinch mentioned are now in the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum (fig. 1) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (fig. 2). Until the early twentieth century, both of these portraits descended in the family of Griselda Eastwick Cunningham (1810–1873), Morton’s granddaughter, who married Rev. Joseph Hart Clinch (d. 1884).38 The Worcester Art Museum’s portrait Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton), which Clinch indicated was unknown to the family, was found in Stuart’s studio after his death, and in 1862 Jane Stuart sold it to Ernest Tuckerman of Newport, Rhode Island.39

Worcester’s Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton) is not only very different from the portraits at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Winterthur, but also atypical of Stuart. At first glance, the head in the Worcester portrait appears as finished as those in the other two portraits, but her eyes, nose, and especially her mouth are blurred. Instead of the stiff and formal pose seen in the other portraits, Stuart captured a very spontaneous gesture of the sitter adjusting her veil. Is Morton dressing to go out, or removing her veil to greet the viewer? The gesture is enigmatic. The viewer is glimpsing a private and personal moment, which contributes to the success and uniqueness of the portrait. On this occasion the poet was the artist’s muse.

Worcester’s Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton) is also different from Stuart’s other unfinished portraits. Stuart was known to have left portraits unfinished; moreover, many of his fully painted portraits are unevenly finished. In the completed Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp) (fig. 2), for instance, the cursory manner with which Stuart painted the shawl covering Morton’s left arm and the sheer kerchief tucked into the bodice of her dress suggests their secondary importance to the sitter’s face. Stuart considered the head the most important part of the composition.40 He therefore probably considered the apparently unfinished portraits Washington Allston (about 1820, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Jared Sparks (about 1826, New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, Connecticut), which were just heads, finished enough for his purposes. These portraits were also found in Stuart’s studio at his death, along with Worcester’s Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton).41 The Worcester portrait, however, depicts more than just a head: Stuart painted the background and blocked in the costume. He built up the composition not by an outline but with color applied in loose and fluid brushstrokes. Stuart had also developed her portrait beyond the head before he drastically changed the original composition.

The Worcester portrait’s pentimento of Morton’s proper left arm across her stomach indicates that Stuart’s initial pose was more in keeping with the traditional pose of the sitter in the other portraits.42 He began with the face, hair, dress, and arms. What caused him to abandon his original plan and paint the present spontaneous and unprecedented alternative and exactly when he did so will never be known.43

Winterthur’s panel portrait of Morton (fig. 1) depicts Morton seated at a table arranged with paper, two books, and a quill pen in an inkstand. Her lips and right cheek are bright red. She wears a black dress with a low neckline and short sleeves. Her thick, brown hair is elaborately curled and arranged high on her head and cascades down her back. The sleeves and neckline of her dress are trimmed with white lace. A long pearl necklace is looped around her neck three times. With the second and third fingers of her proper right hand, she touches the pearl strands of a bracelet on her proper left wrist. The third and fourth fingers of her proper left hand, with a gold wedding band on the latter, touch in an unusual gesture. Her fingers appear unnaturally thin and elongated. The oversize bust of Washington to her right appears in no other portrait painted by Stuart. Although Morton is fastening a bracelet and not engaged in writing, she is portrayed as an author surrounded by the tools of her trade and sitting within sight of her muse, the late president of the United States, to whom she paid tribute in her 1797 poem "Beacon Hill."44

In the Boston oil on canvas (fig. 2), Morton is also seated and turned to the viewer’s left.45 Her lips are a more subdued pink. Again, she wears a black dress with short sleeves. A kerchief of sheer lace is modestly tucked into the bodice. Lace, less abundant than in the Winterthur portrait (fig. 1), is fastened to her left sleeve with a red pin. Besides this pin and her wedding ring, it is not immediately apparent that she is wearing any other jewelry. However, two strands of pearls around her neck that were painted over now appear as pentimenti. Her hair is worn in a bun instead of hanging loose. Strands of hair fall on her forehead and frame her face as they do in the other two portraits, but in none of the three do they fall in exactly the same places. A fringed silk shawl, broadly painted with strokes of green, peach, and gray, covers her proper right arm and is draped over a red upholstered chair, which has a taller curved back than the chair in the Winterthur portrait (fig. 1). Morton’s proper left arm is parallel to the picture plane, her hand resting upon a table with only two books. The background is very dark and plain.

|

|

Figure 3. Gilbert Stuart, Counsellor John Dunn, about 1798, oil on canvas, 29 1/8 x 24 3/8 in. (74 x 61.9 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of Martin Brimmer, 06.2427. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reproduced with permission. © 2000 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved.

|

|

In his 1902 letter to the Worcester Art Museum, John Morton Clinch stated that the portrait of Mrs. Perez Morton on panel (fig. 1), which he called a copy of the portrait on canvas (fig. 2), "was made by Stuart for an admirer of Mrs. Morton."46 Stuart’s earliest biographer, George Mason (1820–1894), stated that this panel was the second portrait and painted without sittings "at the request of Counsellor Dunn, and at his death the family sent it to Mrs. Morton." Unfortunately, little is known about John Dunn, a barrister who represented Randalstown, County Antrim, in the Irish House of Commons from 1790 until 1797, when he visited the United States.47

Sarah and Perez Morton similarly owned a Stuart portrait of Dunn (fig. 3), which he presumably gave her in exchange for hers. In this portrait a bright light focuses attention on the balding head of a middle-aged man, set against a dark background. His right hand touches the fur trim on his red robe. According to a receipt, Sarah Wentworth Morton sold Counsellor John Dunn to George W. Brimmer less than a month after Stuart’s death in 1828.48 It also appears that Dunn, himself, might have died in 1827, before she sold the portrait.49

John Dunn likely shared Sarah Wentworth Morton’s interest in poetry, but the circumstances of their friendship and the reason they exchanged portraits are not known. Perhaps her first long poem, Ouâbi or the Virtues of Nature, An Indian Tale. In Four Cantos, might have caught Dunn’s attention when it was reviewed in the September 1793 London Monthly Review. Dunn had arrived in the United States around the time Morton published "Beacon Hill," and his name appears on George Washington’s personal copy of the poem, which he appears to have sent Washington:

The charming Poem which accompanies this was committed to my care near four weeks ago by Mr. Morton. By delays on the Road I have unfortunately retarded your Perusal of a Poem dictated by Taste and Genius and displaying like its author an exalted Veneration for you. Philadelphia, Jany. 9th 1798.50

The inscription confirms Dunn’s friendship with the Mortons and his admiration for her poetry. After he returned from the United States, Dunn presented a paper to the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin on May 12, 1802, in which he discussed his interest in Native Americans and his attempts to write poetry in an Indian language—yet another bond he shared with Morton.51

Although Morton’s great-grandson, John Morton Clinch, and Mason both stated that the oil-on-canvas portrait (fig. 2) was the original for which Morton sat, neither Stuart scholars nor Morton’s biographers have been able to agree on the dating or sequence of the three portraits. Unlike Dunn, who left the country and never returned, Morton could have sat for Stuart in Philadelphia and after he arrived in Boston in 1805. The art historian Lawrence Park felt the face in the oil on canvas (fig. 2) was a replica of the face in the Worcester portrait.52 In the 1960s scholars Charles Mount and Paul Harris suggested that the two finished portraits were the result of an earlier Philadelphia sitting and that the Worcester portrait was the final of the three and painted in Boston.53 Despite there being no evidence whatsoever, Mount and John Wilmerding went so far as to suggest that Stuart and Morton had an affair, which began in Philadelphia and continued once the artist moved to Boston.54

Harris based his theory on the Worcester portrait’s informal pose and the style of the white dress, which, he believed, dated the work later than the other two. As he and others have pointed out, Stuart painted a portrait of Morton’s daughter, Charlotte Morton (Mrs. Andrew Dexter) (1808, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) in Boston, and Morton could have also sat for him at that time.55

Stuart’s career in Boston did not go unnoticed by Morton. Many from her own social circle, such as the Bowdoins, Hepzibah Clarke Swan and her children, and Henry Knox, sat for Stuart in Boston. Morton paid tribute to Stuart in two poems written after he arrived in Boston and published in My Mind And Its Thoughts in 1823. "Inscription, For The Portrait of Fisher Ames, Painted Con Amore By Stuart," praised Stuart’s sitter, a Federalist United States congressman, author, and orator from Massachusetts.56 In "Stanzas To Gilbert Stuart, On His Intended Portrait of Mrs. H. The Beautiful Wife Of One Of The Naval Heroes Of the U.S.," Morton apparently challenged Stuart to "catch the enchantment" of his sitter, who has not been identified.57

An exchange of verses between Morton and Stuart was published in the popular Philadelphia journal Port Folio on Saturday, June 18, 1803, and proves at least one portrait had been painted in Philadelphia by this date.58 Furthermore, when Mrs. Morton revised "To Mr. Stuart, On His Portrait Of Mrs. M" for publication in My Mind And Its Thoughts, in Sketches, Fragments, and Essays in 1823, the new title—"To Mr. Stuart. Upon Seeing Those Portraits Which Were Painted By Him At Philadelphia, In the Beginning Of The Present Century"—indicates she did not sit for Stuart before the turn of the century.59 Morton’s biographers have suggested that she accompanied her husband on a business trip to Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., during the winter of 1802–3 and perhaps sat for Stuart at that time. Several other poems included in My Mind And Its Thoughts were written on a visit to Philadelphia, but further research is necessary to document the dates of her trip.60

In her verses in the Port Folio, Morton first praised Stuart’s portraits of military figures, young men, older merchants, and women and then added a note about her own portrait:

E’in me, by no enlivening grace array’d

Me, born to linger in Affliction’s shade,

Hast thou, kind artist, with attraction drest,

With all that Nature in my Soul express’d.

Morton’s last stanza is also tinged with melancholy: "The well earn’d meed with sparing hand deny / And on thy talents gaze with dubious eye." Was she referring to her own career and suggesting that Stuart, like her, might not be as appreciated as he should be? That Stuart and Morton commiserated on life’s hardships is suggested by Stuart’s verse, "Mid varied scenes of life, howe’er deprest, / This blest reflection . . . still shall soothe my breast." After Stuart’s responding verses, the Port Folio’s editor added, "I ardently hope that Mr. Stuart will never experience any of those sorrows to which the pen of the poetess pathetically alludes." Stuart’s humble response "To Mrs. M—" declared his own art of painting inferior to her poetry, and he refused to take credit for her portrait:

Nor wonder, if, in tracing charms like thine,

Thought and expression blend in rich design;

’Twas heaven itself that blended in thy face,

The lines of Reason, with the lines of Grace:

’Twas heaven that bade the swift idea rise,

Paint thy soft cheek, and sparkle in thine eyes;

Invention there could, justly, claim no part,

I only boast the copyist’s humbler art.61

Stuart’s humility notwithstanding, public praise for his portraits, as in these verses exchanged in the Port Folio of June 1803 and Morton’s later book, certainly proved helpful in attracting additional commissions.62

The editor of the Port Folio, Joseph Dennie (1768–1812), writing under the pseudonym "Samuel Saunter," introduced the poems by Morton and Stuart with the following explanation:

I have lately enjoyed of examining one of his most beautiful, captivating, and highly finished performances. I allude to his spirited portrait of the impassioned and ingenuous features of a Lady whose rank is high in the Monarchy of Letters, and whose conversation powers, and attractive graces, are the delight of that society, whom she gladdens by her presence.63

Dennie does not indicate that there is more than one portrait of Morton, and his description of the portrait as "highly finished" argues that he was commenting on the panel portrait now at Winterthur (fig. 1). Morton’s original poem title also mentions only one portrait. Worcester’s portrait, which would have been seen as unfinished according to the standards of the day, was certainly not the portrait Dennie praised. The panel portrait (fig. 1) represents Morton as elegant and sophisticated, with an elaborate hairstyle, pearls, and an intricate bracelet.64 The pen, inkwell, and paper would have better suggested her literary career than the two books in the canvas portrait (fig. 2). Further, the bust of George Washington in the panel portrait (fig. 1) can be seen as a specific reference to Morton’s "Beacon Hill," which Stuart likely had in mind with his insistence that her verses "give the chief a deathless name."65

Although the Port Folio article offers some clues about Morton’s sitting for Stuart and suggests theories about the sequence of the three portraits, nothing can be resolved with certainty. Stuart could have been working on more than one portrait of Morton at the same time, even though it appears that the Winterthur panel (fig. 1) was the portrait discussed in the Port Folio. It is unknown when the panel portrait of Morton was sent to John Dunn or whether he personally brought it to Ireland. Did Dunn encourage Morton to sit for Stuart? The original, more traditional pose that is visible in the Worcester portrait implies that Stuart began this portrait as a commission. Was it started in Philadelphia, and did Stuart discard the Worcester portrait and then begin the Boston portrait (fig. 2) as a substitute for a commission? All three portraits are of similar dimensions, but how are the differences in the hairstyles, costume and accessories explained? Was the Worcester portrait reworked later in Boston, given that no veils appear in Stuart’s Philadelphia portraits? Why did Stuart chose a white dress for the final version of the Worcester portrait? There are more questions than answers.

Undoubtedly, Morton was not a dull sitter Stuart was obliged to paint. Her intelligence and beauty inspired him to answer her praise with poetry of his own, with a skill that is not surprising. Stuart’s ability to be witty, charming, and engaging with sitters in his portrait studio is well documented. As Morton’s daughter Sarah Morton Cunningham described a visit to the artist’s studio in 1825:

We saw Stuart himself, as eccentric, as dirty, & as entertaining as ever. He was in one of his best humours, & nothing can be more amusing than his conversation when that happens to be the case, for he seems to think that his genius gives him a right to follow the entire bent of his temper & spirits, be that what it may. We happened to be fortunate in our visit—he was evidently much pleased at seeing s, opened a bottle of some extraordinary Port that had been sent to him as a present, which he insisted upon our tasting, carried us into his painting room to look at his portraits, and omitted no opportunity for punning.66

Stuart was interested enough in the poet to paint the "highly finished" panel portrait (fig. 1) and complete another version on canvas (fig. 2). Furthermore, he impulsively created Worcester’s highly original portrait of Morton, which he kept with him for the rest of his life.

The frame on Worcester’s is original and identical to that on John Holker (1815, private collection), another Stuart portrait painted in Boston. The laurel wreath and acanthus ornaments on these frames might be the work of John Doggett (1780–1857), a Boston carver, gilder, cabinetmaker, and framemaker as well as a picture dealer. If Stuart framed Worcester’s portrait of Morton, he probably considered it a finished work worthy of displaying.

Notes

1. The December 1791 issue of the Massachusetts Magazine was the first to refer to her as the American Sappho. Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 52.

2. Ibid., 21, and Wentworth 1878, I, 521.

3. Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 16–17. For the Apthorp house, see Wentworth and Clark 1995, 40, color pl. vi.

4. Noble 1897–98, 290. See "Invocation, To The Shades Of My Ancestors, Wentworth And Apthorp," in Morton 1975, 267–70. In her will she referred to herself as Sarah Wentworth Morton, as she did when she signed her name to her book My Mind And Its Thoughts in Sketches, Fragments, and Essays in 1823. Will of Sarah Wentworth Morton, Norfolk County Register of Probate no.13, 230.

5. Oliver and Peabody 1982, 740.

6. Heitman 1914, 404.

7. For Perez Morton see Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 23–25; Sibley and Shipton XVII, 1975, 555–61; and Noble 1897–1898, 282–93.

8. Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 25. The Annie Haven Thwing Index of Early Boston Inhabitants at the Massachusetts Historical Society lists several deeds for the brick house.

9. Wentworth 1878, I, 522–24; Oliver and Peabody 1982, 600, 609, 611, 618, 623; Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 39; and page torn from family Bible, Morton, Cunningham, Clinch Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, folder for 1754–99. Sarah wrote "Memento, For My Infant, Who Lived But Eighteen Hours" and published it in My Mind and Its Thoughts, in Sketches, Fragments, and Essays. Morton 1975, 255–56.

10. Massachusetts Centinel (Boston), January 15, 1785. For the Sans Souci Club, see Warren 1926–1927.

11. For more on the club see Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 29–30, and DeLorme 1979b, 371.

12. Frances T. Apthorp, letter, diary, and suicide note, to Perez Morton, August 20–27, 1788, Miscellaneous Bound, Massachusetts Historical Society. These manuscripts were published; see McDowell 1932. For more on the scandal, see Sibley and Shipton XVII, 1975, 557–58, and Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 32–40.

13. Massachusetts Centinel (Boston), October 8, 1788.

14. Herald of Freedom and the Federal Advertiser (Boston), October 13, 1788.

15. The Herald of Freedom and the Federal Advertiser (Boston) stated that the novel was intended to instruct young ladies on the consequences of seduction and "that one of the incidents upon which the Novel is founded, is drawn from a late unhappy suicide." Herald of Freedom and the Federal Register, January 16, 1789. For more on the novel see also the Herald of Freedom and the Federal Register, February 3, 1789, and the Massachusetts Centinel, February 7, 1789.

16. Although the novel was published anonymously, it has since been attributed to William Hill Brown (1765–1793). Davidson 1986, chap. 5.

17. For Perez Morton’s other activities after the scandal, see Sibley and Shipton XVII, 1975, 560–61, and Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 58–60, 80, 92–96.

18. Since Judith Sargent Murray (1751–1920) had written under the same pseudonym of "Constantina" several years before she did, Morton eventually changed hers to "Philenia." Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 42–43.

19. London Monthly Review, September 1793, and Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 46, 48. The poem is also discussed in Mary Watson Hutchinson to Elizabeth Watson, April 6, 1791, Hutchinson Watson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

20. "The Tears of Humanity. Occasioned by the Loss of the Question for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in the British Parliament" appeared in the July 1791 issue of the Massachusetts Magazine. "To The Hon. John Jay," published in 1823 but written earlier, praised Jay as president of the First American Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. For this poem see Morton 1975, 139.

21. See reprints of these poems in Morton 1975, 84–87.

22. Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 48, 50, 85–86.

23. Sarah Wentworth Morton, quoted in Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 64.

24. Ibid., 64.

25. Bentley diary 1962, II, 246. William Dunlap also mentions Morton and her writing on a trip to Boston in the winter of 1797. Dunlap diary 1931, 174, 177, 189, 195. For the reception of "Beacon Hill," see also Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 67.

26. Morton 1975, xvi.

27. See list of subscribers in ibid., 291–95.

28. Ibid., 182, 260–61.

29. Ibid., 287–88. There is a large volume of miscellaneous manuscript poems by Sarah Wentworth Morton in the Department of Manuscripts at the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, Calif.

30. Wentworth and Clark 1995, 8, 10.

31. Ibid., 38, and Inventory of the Personal Estate of Mrs. S. W. Morton, [1846], Morton, Cunningham, Clinch Papers, folder for 1840–49.

32. General Advertiser (Philadelphia), November 23, 1791; Sibley and Shipton XVII, 1975, 558–59; and Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 51.

33. Sibley and Shipton XVII, 1975, 561, and will of Perez Morton, Norfolk County Register of Probate, docket no.13, 288.

34. For the Mortons’ residences in Dorcester, see Clapp 1892, and Bentley diary 1962, 11, 201.

35. Quincy Patriot, May 16, 1846; Boston Daily Mail, May 16, 1846; Daily Evening Transcript, May 15, 1846.

36. Will of Sarah Wentworth Morton, Norfolk County Register of Probate no. 13, 230.

37. J. Morton Clinch, April 3, 1902, Boston, to the curator of the Museum of Fine Arts, Worcester, April 3, 1902.

38. Sarah Wentworth Morton survived all of her children. An inventory of her estate listed "8 Family portraits" valued at four dollars and another portrait valued at five dollars. Inventory of the Personal Estate of Mrs. S. W. Morton, [1846], Morton, Cunningham Clinch Papers. Her granddaughter Griselda was the daughter of Sarah Apthorp Morton Cunningham. After Griselda’s death, both portraits descended to her husband, who was recorded as the owner in Mason 1879, 225. After he died in 1884, the portraits were divided among his children. According to Park 1926, II, 537, the portrait Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp) (fig. 2) passed to his daughter Sarah Apthorp Cunningham Clinch Bond (1835–1914), who sold it to her sister Mary Griselda Clinch Fogg (1840–1905) about 1890. Mary Fogg loaned it to the Copley Society in 1902. Copley Society 1902, cat. no. 66. At her death, the portrait was bequeathed to her older sister Mary Josephine Clinch Gray (1837–1905), whose daughter Frances Uniacke "Una" Gray sold it in 1916 to Grace Edwards and her sister Hannah Marcy Edwards. The latter bequeathed the portrait to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1939. BMFA 1969, I, 245.

At the death of Joseph Hart Clinch, the portrait Mrs. Perez Morton (Sarah Wentworth Apthorp) (fig. 1) descended to his daughter Mary Josephine Clinch Gray (1837–1905) and then her daughter Mary Griselda Gray. Park 1926, II, 538. It appears to have been in the possession of Una Gray when it was sold to the Ehrich Gallery in Boston about 1927. It was later sold to the Helen Hackett Gallery and entered the collection of John Hay Whitney. In 1963 the portrait was acquired by Winterthur. Harris 1964, 202, and Richardson 1986, 94.

39. In the inventory of his estate, "8 unfinished sketches of Heads" were found in the front chamber of Stuart’s house. Probate inventory of Gilbert Stuart, Suffolk County no. 28699. Harris incorrectly interpreted the exhibition catalogue for the 1880 exhibition of Stuart portraits at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and concluded that there were four portraits of Morton. Harris 1964, 203, 206. The catalogue included a complete checklist of known Stuart portraits adapted from Mason 1879, and only one of the two portraits of Morton on the checklist (listed as 418 and 419) was actually exhibited (as cat. no. 232) in the exhibition. BMFA 1880, 11, 48.

40. Stuart’s statement, "I copy the works of God and leave clothes to tailors and mantua makers," is often repeated. Quoted in McLanathan 1986, 144.

41. Not all of Stuart’s unfinished portraits were from late in his career. Stuart’s portrait Counsellor John Dunn also remained unfinished in his studio at his death. Parke-Bernet 1947, 24, and Miles 1995, 218.

42. Stuart typically worked very quickly, and it was unusual for him to make changes as a portrait progressed, but there are other examples of him doing so. For instance, in his portrait of Morton’s friend, Sally Foster Otis (Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis) (1809, Reynolda House, Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina), Stuart had originally posed the sitter with her left arm around her son’s shoulders, but he later painted the child out. Feld 1999, 108, cat. no. 64.

43. Richard McLanathan’s suggestion that the Worcester portrait might have been done for "friendship’s sake" and not as a commission is unlikely given the original pose, which is related to the others. McLanathan 1986, 111–12.

44. Morton had sent Washington a copy of her poem personally inscribed,"To George Washington—A Name honoured in History—Loved by the Muses—and immortal as Memory—The following Poem, originated by Enthusiasm, is presented with Diffidence from The Author." Quoted in Wentworth and Clark 1995, 42.

45. For the Richard Morell Staigg (1817–1881) miniature copy of this version of the portrait, see Mrs. Perez Morton (about 1840–50, The New-York Historical Society) in New-York Historical Society 1974, II, 564–65.

46. Mason 1879, 225.

47. According to Jane Stuart, Dunn was close friend of her father’s. Miles 1995, 216–18. It is possible that Stuart had met Dunn when he was in Ireland.

48. Park quoted the receipt found in the papers of George Brimmer Inches (d. 1919): "Mr Geo W. Brimmer/Bo’t of Perez Morton./The Portrait of Counsellor John Dunn Member of the Irish Parliament painted by Gilbert Stuart about 1798. $150/Dorchester 4 August 1828/Rec’d Payment for P.M./Sarah Wentworth Morton/I acknowledge the above receipt to be good—being appropriated to her use.—Perez Morton." Park 1926, I, 295.

49. Apparently Dunn’s name disappeared from the Dublin directories after 1827. Miles 1995, 216–18, n. 11. It is worth noting that Stuart painted two other portraits of Dunn. A canvas closely related to the portrait owned by the Mortons, except for a slight difference in gesture and finish, was owned by Dunn’s descendants (about 1798, National Gallery, Washington, D.C.) and is presumably the one he took back to Ireland with him. Unlike the portraits of Morton, the similarities of these two portraits of Dunn leave no doubt that they were both the result of the same 1798 sitting in Philadelphia. The third portrait of Dunn is an unfinished panel of only his head, and its dimensions are smaller than the other two canvases. Like Worcester’s Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton (Mrs. Perez Morton), the panel portrait Counsellor John Dunn (1798, private collection) was found in Stuart’s studio at his death. It could not have been painted much later than the other two portraits, since Dunn had returned to Ireland by March 1802, but whether it preceded one or both portraits is impossible to know. What is certain is that Stuart valued the unfinished head enough to take it with him when he left Philadelphia. For the unfinished portrait of Dunn see Park-Bernet 1947, 24, and Miles 1995, 218. The portrait has a canvas stamp, which suggests that this portrait is not the copy by Jane Stuart that was exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum in 1847. Katlan 1987, 149, 413; Perkins and Gavin 1980, 137.?

50. Sarah Wentworth Morton, quoted in Harris 1964, 218. George Washington’s copy of "Beacon Hill" is in the library of the Boston Athenaeum. P. Griffin 1897, 147.

51. Dunne 1803.

52. Park 1926, II, 536, cat. no. 562.

53. Mount 1964, 276; Harris 1964, 206; DeLorme 1979b, 378, n. 56.

54. Mount 1964, 242–48, 275–76; and Wilmerding 1976, 51–52.

55. A page torn from Stuart’s account book indicates that Charlotte Morton sat for her portrait in April 1808, before her upcoming marriage to Andrew Dexter (1779–1873) in June of that year. "Mrs. Morton" is also listed in Stuart’s account from April 28, 1808. Swan 1938, 308.

Stuart painted Charlotte’s face and shoulders and indicated her hair and white dress. For unknown reasons, the portrait was still incomplete when Morton and another daughter, Sarah Morton Cunningham, saw it in Stuart’s studio in 1825. Sometime after this date, it was finished by an unidentified artist, who updated the style of the dress and hair to reflect current fashions. For Charlotte Morton (Mrs. Andrew Dexter) (1808, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), see Miles 1995, 279–81. There is also a Stuart portrait of Andrew Dexter (unlocated), but it is not a companion portrait. Antiques 103 (March 1973): 449.

Charlotte Morton Dexter died in 1819. Her sister Sarah Morton Cunningham wrote to her daughter after seeing this portrait, "What would I not give to have in my power to complete and to possess this interesting portrait." Sarah Apthorp Morton Cunningham, Dorchester, to Griselda Eastwicke Cunningham, Saulsbrook, Nova Scotia, April 11, 1825, Morton, Cunningham, Clinch Papers.

56. Morton 1975, 76.

57. Morton wrote, "I charge thy genius, let it be, / Reflecting HER, and speaking THEE." Ibid., 213–14.

58. Verses quoted in Saunter 1803, 185. Stuart left New York for Philadelphia in March 1795, intent on securing a sitting from President Washington. In addition to painting portraits, Stuart was kept busy in Philadelphia with commissions for copies of his portraits of Washington, whose death in 1799 increased his orders. Business eventually slowed, however, after the transfer of the nation’s capital to Washington, D.C., and Stuart decided to follow it in December 1803. McLanathan 1986, 114.

59. She also generalized the four-line reference to her portrait by substituting the words "Even one" for "E’in me." Instead of "Me, born to linger," she wrote "One, born to linger." See Morton 1975, 74–76.

60. Perez Morton was charged with conveying petitions to President Jefferson and Congress regarding land in Georgia owned by Bostonians. Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 80. See also Morton’s "Song. Written At ‘The Woodlands,’ The Seat of William Hamilton, Esq. Upon The Schuylkill," in Morton 1975, 77.

61. Verses and Port Folio editor, quoted in Saunter 1803, 185.

62. Jessie Poesch demonstrated that poems, including poetry about artists and their paintings, were part of popular culture in eighteenth-century America and that they had English prototypes. Poesch 1993. Morton and Stuart were obviously acquainted with this practice. Stuart was not the first artist she praised. In January 1793, "To Pollio" appeared in the Massachusetts Magazine. This tribute to the artist John Trumbull (1756–1843) was later revised under the title, "Lines Inscribed To A Celebrated Historical Painter, Upon His Return From Great Britain To The United States." Massachusetts Magazine 5 (January 1793): 52, and Morton 1975, 49–50. Stuart and Morton’s exchange in the early nineteenth century followed this English precedent. Saunter 1803, 185.

63. Saunter 1803, 185. According to Pendleton and Ellis 1931, 85, Samuel Saunter was a pseudonym for Joseph Dennie, the editor of the Port Folio.

64. A similar dress, upholstered armchair, and bracelet appear in Arabella Maria Smith Dallas (Mrs. Alexander James Dallas) (1800, unlocated), another Stuart portrait of a Philadelphia sitter, and help confirm the Philadelphia origin of the panel portrait. Sotheby’s 1994, lot 13. Stuart’s Abigail Willing (Mrs. Richard Peters) (about 1803, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia), of another Philadelphia sitter, also has a pen, inkwell, and papers.

65. Gilbert Stuart, quoted in Saunter 1803, 185.

66. The letter continues to describe the artist’s wit and comments on the unfinished portrait of Charlotte Morton (Mrs. Andrew Dexter). Sarah Apthorp Morton Cunningham, Dorchester, to Griselda Eastwicke Cunningham, Saulsbrook, Nova Scotia, April 11, 1825, Morton, Cunningham, Clinch Papers. |