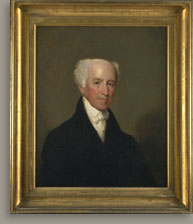

Gilbert Stuart Gilbert Stuart Samuel Salisbury, 1810–11 Description Salisbury's eyes are blue-gray, with tiny white highlights in the upper left of each pupil. The inside of the lower lid of the proper left eye is highlighted with a pale flesh color and a tiny white dot, and a triangular area of pink colors the corner. The proper right eye is rimmed with pink. Stuart extended the iris slightly over the eyelid in both eyes. Fine brown lines in the right corner of both eyes suggest wrinkles. The eyebrows were painted with strokes of various sizes in brown and gray. The flesh paint is thicker on the forehead and the bridge of his nose. A white highlight runs along the length of his long, curved nose, and a shadow is cast to the left of the nose. His upper lip is barely discernable, and his small, slightly pink lower lip is very pinched, suggesting that he has no teeth. He has a double chin. His cheeks are red, and the red glaze from the face is painted over the wig on the right side of the face. Salisbury wears a black coat with a large, high collar. Four buttons, covered in black fabric, are visible on the right of the coat, which is fastened across the middle with only one button. Broad strokes of dark gray paint were used for the coat; the shadows along the contours of the sleeves, the lapel, and collar were painted with black. The outlines of the buttons and the creases at the elbows, upper arm, and across the front of the coat were also painted with black. There is impasto on the white ruffle of the neck cloth. The ruffles on the left side of the neck cloth were loosely painted over the black paint of the coat, creating a light blue color. Salisbury is seated, with his proper left arm parallel to the bottom of the picture. A small stroke of white painted on top of the flesh of his proper left wrist suggests the cuff of his shirt. His proper left hand, which rests on his proper left thigh, was painted on top of the black paint of the coat. The thumb, with a pink highlight, and the first and second fingers are barely defined, with subtle shadows between them. The remaining fingers are not shown and appear to be curled inward, making his hand appear slight and feeble. His black breeches are visible where his coat is open. Salisbury sits in an armchair of blond wood with solid upholstered panels of red fabric. A small portion of the chair's curved, low back is visible on the right side. The sides of the chair taper toward the arm, with the ends turned outward. There appears to be red drapery hung over the right arm of the chair, which has faded so that the red strokes seem to be on a gray background. The same thing has occurred to the drapery on the left arm of the chair, which is now only a gray area. Stuart outlined the curved arms and the back of the chair in brown after he painted the blond wood. Scattered yellow highlights appear on the wood. The dark paint and the red paint of the chair overlap the paint used for the figure, which suggests that the chair was painted after the figure was completed. The background of the portrait is olive and is darker behind the sitter and in the upper part of the painting. Biography Samuel married Elizabeth Sewall (1750–1789) on September 29, 1768. She was the daughter of Elizabeth Quincy and Samuel Sewall (1715–1771), a merchant and deacon of the Old South Church. Although Samuel inherited his father's Marlborough Street house in Boston, his mother, Martha, had the use of it until her death.4 During the early years of his marriage he complained to Stephen:

Samuel's pleas continued in other letters, but his wish did not come true immediately. When the Revolution forced him to close the Boston store in 1775, Worcester provided a safe haven for him and his family and some of the other Boston Salisburys, including his widowed mother and unmarried sister Sarah (1745–1828).6 Samuel's letters to Stephen written before he left Boston document his reactions to the events leading up to the Revolution and their effect on his business. On December 17, 1773, for instance, he described the meeting at "Griffins Wharfe where lay the 3 ships with Tea on Board, and before 9 oClock it was all destroy'd by breaking open the Chest & Shovells & pouring out into the sea. what the consequences of these proceedings time will discover. God grant they may be happy."7 S. & S. Salisbury continued to operate in Worcester during the Revolution. A Worcester newspaper advertisement from July 1778 listed hardware, as well as brandy, sherry, coffee, chocolate, spices, wood, wool and pewter.8 In 1784, Samuel's family, which had grown from three to seven children, returned to Boston to reopen the Boston store. Martha Salisbury remained in Worcester with Stephen until her death in 1792. Although the original plan appears to have been to bring Martha Salisbury to Boston in the spring of 1784, she remained with Stephen. This might have been intentional on Samuel's part.9 Samuel and Elizabeth Sewall Salisbury had ten children before Elizabeth died unexpectedly on March 25, 1789. Samuel did not remarry until a number of years later.10 His partnership with Stephen continued until his death, although the Boston branch of their hardware store appears to have closed sometime after 1807. Samuel continued to manage their investments.11 He became a member of the Old South Church in 1790, though he had been active in church affairs since his return from Worcester. In 1794 Salisbury was chosen to be a deacon, and he served until his death. His name appeared frequently as a member of committees appointed to examine accounts of the church treasurer.12 In 1791 he was elected a selectman of Boston.13 He was also a member of the Massachusetts Agricultural Society.14 On November 7, 1812, Samuel married Abigail Treeman Snow (d. 1858) of Boston. Snow is mentioned in family letters after Samuel fell and severely injured his leg in January 1811.15 Stephen Salisbury went to visit Samuel in Boston and reported to his wife, "I shall be loath to leave my brother till he is in a hopeful way of Recovering, though I dont know I do him any good for Miss Snow is a very careful and attentive nurse-and a very even tempered woman."16 Samuel recovered and purchased a new house on Chestnut Street at the end of May 1811, likely in preparation for his upcoming marriage to Snow. His house on Marlboro Street, where his store had been for years, was rented.17 Near the end of Samuel's life, family letters express concern about his second wife, her unkindness to him and his children, and her plot to gain control of his estate.18 Samuel died on May 2, 1818. His obituary appeared first under the column of "Deaths" in the Columbian Centinel: "In this town, on Saturday, SAMUEL SALISBURY, Esq. aged 78. His life was full of good deeds."19 Samuel was buried in his tomb in King's Chapel Burial Ground.20 The inventory of his estate was valued at more than $400,000. Samuel and Stephen Salisbury had jointly owned stocks, real estate, and other investments, and Samuel's heirs settled the accounts and paid Stephen $250,000 as his share.21 Analysis Although it is not known when Samuel sat for Stuart in Boston, family letters indicate that his sittings had been completed by February 1811 and that the family was waiting for his portrait as well as Elizabeth's. At that time, Stephen was in Boston visiting Samuel, who had seriously injured his leg. After a trip to Stuart's studio, Stephen wrote home to Elizabeth about the portraits' status: "Steward says it would not due to Varnish the Pictures until the Snow is gone, so that he don't intend we shall have them until the Spring—"23 At the end of April, after visiting Stuart, Samuel's son Josiah wrote to inform Stephen and Elizabeth that Stuart said the portraits were finished and ready to be delivered. He offered his assistance in forwarding them.24 Josiah's announcement turned out to be premature. Samuel wrote on May 8 that "I saw Stewart on Monday he said the Pictures were not Varnish'd but he would do them directly if ready they shall be sent up by Howard—"25 The portraits were not sent, and an exasperated Josiah wrote to his uncle on May 11, "Have been endeavoring to get the pictures from Stewart's. very little dependence can be placed upon anything he says. When I first called upon him, he assured me without hesitation, that they were completed, & ready for delivery—& yet, it afterwards appeared, that they were not varnished.—I Shall attend to it & as soon as they are actually finished, Mr. White shall make a Case for them."26 Josiah's next letter to Worcester, sent three days later, explained that Stuart's wife said the artist was ill and unable to answer any questions. Whether Stuart was actually ill or had run out of excuses, the Salisburys waited about a month longer for the portraits. On May 15, 1811, Samuel wrote to Stephen of the completion of two Stuart portraits of him. He explained that after his daughter Rebecca Salisbury Phillips (Mrs. Jonathan Phillips) decided which portrait of him she wanted, the other would go to Stephen. Samuel told Stephen, "I have not been able to get the Portraits-I believe they better lay there for the present—as Becca is now gone I can make no choice—"27 This is the first indication that Stuart painted a replica in addition to the portrait of Samuel that Stephen commissioned. It is also clear that Samuel did not intend to keep a portrait of himself. Unlike Stephen, who had sat for Christian Gullager for his own portrait in 1789 and who would sit for Stuart in 1823, Samuel did not commission his own portrait.

The portraits Stephen Salisbury commissioned of his brother and wife, Samuel Salisbury and Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (Mrs. Stephen Salisbury I) (fig. 1), function as companion portraits, but it appears that Stephen chose to frame them differently.35 Both portraits are on mahogany panel and have similar dimensions. Samuel and Elizabeth are both seated. The backgrounds of the portraits are the same olive color. The chair in their portraits, which appears with variations in many other Stuart portraits, is likely a studio chair or product of Stuart's imagination. Samuel's chair shows a low, curved back, and it is upholstered in a brighter red fabric than that in Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (Mrs. Stephen Salisbury I). According to Thomas Michie, curator of decorative art at the Rhode Island School of Design's Museum of Art, these chairs resemble an English or American version of the French bergère-type armchair.36 This unusual chair is often shown with fancier gilded arms, with and without a low or high rounded back, and upholstered in rose, red, green, or black.37 Sally Foster Otis (Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis) (1809, Reynolda House, Winston-Salem, North Carolina), Hepzibah Clark Swan (Mrs. James Swan) (about 1806–10, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Adam Babcock (about 1806–10, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) are just a few examples of Stuart portraits of Boston sitters painted about the same time as the Salisburys, who are represented in this chair. Five years after Samuel's death, his son Josiah wanted a replica of his Stuart portrait. He also persuaded his uncle, Stephen, to sit for Stuart so that he could obtain a replica of his portrait. Josiah was not the first to want a copy of his father's portrait.38 In 1813 another family member had commissioned Gilbert Stuart Newton (1794–1835) to copy Stuart's bust-length portrait of Samuel.39 In his July 17, 1823, letter to Stephen, who had just returned to Worcester after sitting for Stuart, Josiah wrote, "I have just called at Mr. Stewarts' rooms, & find he has not yet made a beginning on the copies, but have encouragement, that it will not be delayed beyond the next week."40 Unfortunately, Josiah's hopes for Stuart to quickly finish the original portrait of his uncle and begin the replica of it as well as a replica of his father's were short-lived. On August 21 Josiah again mentioned the portraits to his uncle in a letter: "I have called, three times, upon Stuart without being able to see him. He has lately removed to Essex street, which, I suppose has interrupted his labors. I think, however, he considers your portrait as finished, except the varnishing, & I hope to have a fine copy of yours and my father's."41

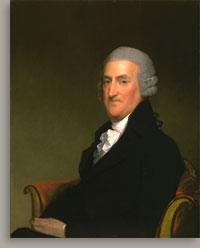

In 1885, Edward Elbridge Salisbury (1814–1901), the grandson of Samuel Salisbury and the son of Josiah Salisbury and his wife, Abby Breese, was the first to suggest that Stuart's bust portrait of Salisbury (fig. 2), chosen by Rebecca Salisbury Phillips, is "supposed to be the original of all." Edward had received this portrait from his uncle Jonathan Phillips sometime after his aunt's death.45 Although Samuel had said that Rebecca chose the bust portrait because she believed it was the "best likeness," nothing was written to indicate that it was Stuart's original portrait.46 Contrary to Lawrence Park's statement that Samuel was shown seated in a chair in Rebecca's bust portrait, no chair is visible.47 In the bust portrait, a tan-colored wall with a pilaster is visible to the right of the sitter and broadly painted red drapery to the left. The sitter's face is turned slightly to the viewer's left, as it is in the portrait Stephen owned, but there are differences. In Stephen's portrait, Samuel's face is turned slightly to the left so that more of the left side of his face is visible. The wig in Rebecca's bust portrait has more hair visible on the left side of the face, less definition in the curls on the right, and the queue ribbon is tied higher on the sitter's head. The black coats are similar, but the ruffle on the neck cloth in the bust portrait is not as detailed. It was loosely and quickly painted with strokes of white over the black of the coat. Although the bust portrait of Samuel Salisbury (fig. 2) is less finished than the larger portrait that Stephen owned, it is impossible to determine which portrait came first, especially since Stuart was occasionally known to have enlarged a smaller original portrait for a copy.48 Notes 2. Salisbury 1885, I, 37, and Suffolk County Deeds, Massachusetts Archives, vol. 61, January 28, 1740, 32, and vol. 71, January 1, 1745, 107. For John Elbridge's will see Salisbury 1885, 124–28. There is a portrait of John Elbridge by an unidentified artist in the Worcester Art Museum, which was also a gift of Stephen Salisbury III (1901.26). 3. Salisbury 1885, 38, and Jenks 1886, 62, 70, 76. 4. Will of Nicholas Salisbury, April 4, 1748, Suffolk County no. 9164. 5. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, July 12, 1769, Salisbury Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society (hereafter cited as SPF, AAS), Worcester, Mass., box 2, folder 1. 6. Samuel Barrett, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 3, 1775, SFP, AAS, box 3, folder 3, and Salisbury 1885, I, 42. 7. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, December 17, 1773, SFP, AAS, box 2, folder 5, and Nichols 1925. 8. Thomas's Massachusetts Spy or American Oracle of Liberty (Worcester), July 2, 1778. 9. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, December 30, 1783, SFP, AAS, box 4, folder 5. 10. Samuel Barrett, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, March 25, 1789, SFP, AAS, box 5, folder 6. For the children of Samuel and Elizabeth Sewall Salisbury, see Salisbury 1885, I, 53, 58, 60, 62, 65, 70–71. See also Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, April 1, 1789, Salisbury Family Papers, Manuscripts and Archives, Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., series 3, box 13, folder 139. 11. According to the Boston city directory, trade in the Boston store appeared to have ended before Samuel's death. Salisbury 1885, I, 33. 12. Hill 1890, II, 258–59, 410. 13. Boston Town Records 1903, 250. 14. Massachusetts Agricultural Society 1801, 92. 15. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, January 21, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 14, folder 7. 16. Stephen Salisbury I, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 4, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 1. 17. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 27, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 2. 18. Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, to Josiah Salisbury, Boston, [March 15, 1818], SFP, AAS, box 18, folder 1. 19. Columbian Centinel (Boston), May 6, 1818. 20. In September 1789 it was decided at a meeting of Boston selectmen that "Liberty is granted to Mr Samuel Salisbury, to build a Tomb in the Chapel Burying Ground." See Boston Selectman's Minutes 1896, 103, and Bridgman 1853, 150–51, 253–54. 21. Samuel Salisbury, will and inventory, Suffolk County probate record no. 25522. See also Heirs of Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, May 12, 1818, Salisbury Family Papers, Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Mass. In Stephen's quitclaim agreement dated July 25, 1818, he indicated that he received the sum in "stocks, notes, bonds, and mortgages, and also a general release of Real Estate in Worcester County and other articles of property not of great value in full for my share of the joint estate, property, and effects." Quitclaim Agreement, Salisbury Family Papers, Worcester Historical Museum. Thanks to Holly Izard for these references. 22. Copy of Gilbert Stuart's receipt to Stephen Salisbury I, November 8, 1810, in the hand of Stephen Salisbury III, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 3. According to a note by Stephen Salisbury II, Stuart's Stephen Salisbury I cost one hundred dollars. Stephen Salisbury II, Memoranda of Portraits, SFP, AAS, Octavo vol. 62, 37. 23. Stephen Salisbury I, Boston, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Worcester, February 11, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 1. 24. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, April 30, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 2. 25. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 8, 1811, in ibid. 26. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 11, 1811, in ibid. 27. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, May 15, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 2, and Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 14, 1811, in ibid. 28. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, May 27, 1811, in ibid. 29. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, May 30, 1811, in ibid. 30. Rebecca Salisbury Phillips's portrait of her father (fig. 2) went to her nephew Edward Elbridge Salisbury (1814–1901), of New Haven. He gave it to his nephew Theodore Salisbury Woolsey (1852–1929), of New Haven, who gave it to his niece Laura Woolsey Heermance, of New Haven, who owned it in 1926. Sometime after her death around 1967, the portrait was given to her niece Laura Endicott, who gave it to her daughter Heidi, for whose benefit it was purchased from Sotheby's in October 1981 by the Worcester Historical Museum. Park 1926, II, cat. no. 725; Salisbury 1885, I, 47; William B. Gumbart, Jr., Trust Officer, First New Haven National Bank, to Louisa Dresser, February 21, 1967, Worcester Art Museum curatorial files (hereafter WAM files), Worcester, Mass.; Thomas Peck, Sr., Trust Officer, First Bank New Haven, to Susan Strickler, August 3, 1981, WAM files; Richard S. Nutt, to Adele Woolsey, February 10, 1998, WAM files; Richard S. Nutt, to Laura Mills, March 17 and 21, 1988, WAM files; and Sotheby Parke Bernet Inc. 1981, lot 1. 31. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, June 18, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 2. 32. Ibid. 33. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, May 27, 1811, in ibid. 34. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, June 18, 1811, in ibid. 35. Stephen informed Elizabeth that in her absence he was having her "Picture fraim new Gilt." Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, to Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury, Boston, October 30, 1811, SFP, AAS, box 15, folder 3. 36. Thomas S. Michie, Curator of Decorative Arts, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, to Laura Mills, May 6, 1998, WAM files. See examples in Montgomery 1966, 175–77. 37. DeLorme 1976, 127. 38. Josiah's son Edward Elbridge Salisbury (1814–1901) recalled that Stephen Salisbury sat to Stuart "at my father's solicitation." Salisbury 1885, I, 34. 39. Blake Ashburner to Susan Strickler, July 8, 1983, WAM files, and Salisbury 1885, I, 47. The current owner of this portrait is unknown. 40. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, July 17, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 2. 41. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, August 21, 1823, SFP, AAS, box 21, folder 2. 42. Josiah Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, January 29, 1824, in ibid. 43. Stephen Salisbury I, Worcester, to Josiah Salisbury, Boston, February 17, 1824, Salisbury Family Papers, Yale University, series 3, box 12, folder 117. 44. Both portraits are in identical frames. For the provenance of Josiah Salisbury's portrait Stephen Salisbury I, 1824, see the catalogue entry for Stuart's original portrait of Stephen Salisbury I. Josiah's portrait of Samuel Salisbury was inherited by his widow Abby Breese Salisbury, who died in New Haven in 1866. Her will, written in 1855, bequeathed the portrait to her grandson Theodore Salisbury Woolsey (1852–1929) of New Haven. At his death, the portrait passed to his son Heathcote Muirson Woolsey (d. 1956) and then to his wife, Dorothy, until her death in 1962. It then passed to her son Theodore D. Woolsey of Bethesda, Md., and then to his wife, Adele H. Woolsey. The portrait is now in the possession of her son Timothy D. Woolsey. See Park 1926, II, 660, cat. no. 726; Mrs. Thomas Dixon Walker to the Worcester Art Museum, February 8, 1966, WAM files; Richard S. Nutt to Adele S. Woolsey, February 10, 1998, WAM files; Richard S. Nutt to Laura Mills, March 17 and 21, 1998, WAM files; and George Woolsey to Laura Mills, May 5, 1998, WAM files. 45. Salisbury 1885, II, 47. 46. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, May 27, 1811, SFP, AAS, , box 15, folder 2. 47. Park 1926, II, 659, cat. no. 725. 48. For the two Stuart portraits of James Perkins, see Wentworth and Clark 1995, 50. |