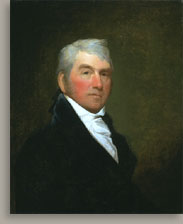

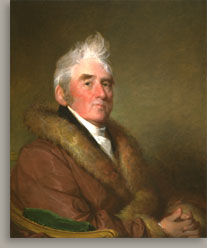

Gilbert Stuart Gilbert Stuart Russell Sturgis, 1822 Description Sturgis wears a reddish brown robe trimmed with reddish brown and gold fur at the collar, sides, and cuffs. The soft texture of the fur is conveyed by the application of grays, yellows, reds, and browns—all blended together. The light and dark highlights on his arm and the body of the robe were painted with large, loose strokes. A black coat and white neck cloth are visible underneath the robe. Sturgis's left arm is parallel to the picture plane and the arm of the chair. His hands rest in his lap. The fingers of each hand are interlaced, his left thumb atop his right. The index finger of his right hand casts a shadow on his left hand. The flesh on his hands consists of oranges and pinks. There are highlights on several nails, and some fingers are outlined in a reddish brown. Small strokes of white on the sitter's left wrist suggest the cuff of his shirt beneath the fur. Sturgis sits in an armchair of blonde or gilded wood upholstered in green velvet. The robe's visibility underneath the arm of the chair indicates that the sides of the chair are not solid wood or upholstered. With brown paint, Stuart outlined the curve of the wood along the top and bottom of the arm as well as the carved handle and a small portion of wood visible on the back of the chair. Opaque yellow highlights are scattered along the arm of the chair. The background is painted with prominent brushstrokes and varies in color from gray to a tan-green. The area just above Sturgis's left arm is a darker gray to suggest the shadow cast on the wall by the sitter's head. In the upper corners of the painting, the background is tan-green. To the right of the sitter's face, the background is the lightest. Strokes of light green appear along the face and the top part of the fur collar. Biography Sturgis worked as a hatter and furrier, as did his younger brother, Samuel (1762-1825). In the Massachusetts Centinel on May 1789, Sturgis advertised, "New fashion in Waistcoats. NEWEST fashion WAISTCOATS, by pattern or invoice, to be sold, very cheap (being a consignment) by Russell Sturgis. Also a general assortment of HATTERS' TRIMMINGS, Carolina Indigo and Rice, per cask, &c. Cash given for all kinds of FURS."6 Of their sixteen children, eight did not survive childhood and three others died very young. Their eldest son sailed for Santo Domingo in the winter of 1790, and neither he nor his ship was ever heard from again. Only their son Nathaniel Russell (1779-1856) and their daughter Ann Cushing (1797-1892), who married Fredric William Paine, left issue that survived to adulthood.7 Sturgis's brother-in-laws, James Perkins (1761-1822) and Thomas Handasyd Perkins (1765-1854) traded along the Northwest Coast and with China as the firm of J & T. H. Perkins. In 1795 Sturgis joined his brother-in-laws and a few others in the ownership of a new ship, the Grand Turk, which was sent to Canton in March 1796.8 When the Perkinses decided to establish a branch office in Canton in 1803, Sturgis invested substantially in the venture.9 Three of Sturgis's sons went to China. Henry (1790-1819) died in Macao at twenty-nine, and George Washington (1793-1826) was in Canton between 1810 and 1823.10 James Perkins (1791-1851) was in Canton and Macao the longest. He arrived in 1809 and died on his voyage home in 1851. In 1818 the three brothers, as partners in the firm of James P. Sturgis and Company, were all involved in the opium trade.11 Among other militia commissions during the Revolution, Russell Sturgis was a lieutenant of the Boston regiment of the Massachusetts militia charged with guarding prisoners under General William Heath at Fort Hill in August and September 1778.12 From 1787 to 1792, he served under John Johnston as first lieutenant of a company of light artillery in Boston. Sturgis's name appears frequently in the Boston records. From 1790 to 1796 he was chosen as one of the fire wardens in Boston.13 In 1792 he was elected to a committee to assess an outbreak of smallpox.14 Sturgis was a Boston selectman from 1796 to 1797 and from 1799 through 1802. He represented Boston in the Massachusetts state senate in 1801.15 He ran unsuccessfully as the Republican candidate for state senator in 1805, though he received the most of his party's votes.16 Sturgis was also involved in education and the arts. In 1797 he and his brother-in-law Thomas Handasyd Perkins were trustees of the School-House on Federal Street in Boston.17 Sturgis was also one of fifty-seven Bostonians to subscribe funds to build the Federal Street Theatre in April 1793, and in 1795-96 he and his brother-in-law James Perkins were on a committee to enlarge the theater.18 Sturgis died on September 7, 1826, two days after the death of his son George Washington.19 His death was noted in the Boston Commercial Gazette: "Mr. Sturgis was a native of Barnstable and of an ancient and respectable family. He came to Boston when young. He was a respectable merchant, an honest man, an ardent patriot, and an affectionate friend."20 Sturgis was buried in the Granary Burial Ground in Boston.21 His wife was named executrix of his estate. Apart from one thousand dollar bequests to his surviving children, the remainder of his estate was given to his wife.22 Although no inventory was filed at the time of his death, one was completed after Elizabeth Perkins Sturgis died on September 8, 1843. At that time her real estate was valued at ten thousand dollars and her personal estate at more than thirty-seven thousand dollars.23 Analysis Though the fur trim on Sturgis's robe is surely a reference to his career as a furrier, it is not unique to his portrait.24 Other Boston portraits of male sitters wearing fur-trimmed coats and robes include Harrison Gray Otis (1809, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Boston), Major-General Henry Alexander Scammell Dearborn (about 1812, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine), and Judge Stephen Jones (about 1820, unlocated).

Sturgis was not the only member of his family to sit for multiple portraits.27 As a widow, Sturgis's wife sat for Chester Harding (private collection) in 1834 and had her profile taken by Auguste Edouart (1789-1861) in 1843 (Worcester Art Museum).28 The Harding portrait of Elizabeth seems to have been painted at the request of James Perkins Sturgis, who wrote from Canton to his sister Betsy on May 1833 to ask her to arrange for their mother to sit for her portrait:

Gilbert Stuart Newton (1794-1835) visited Boston in 1832, but he was not there in January 1834 when James again wrote to his sister to request her help in getting a portrait of his mother. Harding was the chosen substitute.30 While he was in China, James Perkins Sturgis sat for the British artist George Chinnery (1744-1852) for at least two portraits, including one painted around 1840 in the collection of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.31 Chinnery arrived in China in September 1825, and James Perkins Sturgis sent his mother an early portrait Chinnery painted of him (unlocated), which was exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum in 1827.32 Perhaps because Russell Sturgis sat for Stuart on three different occasions during the last twenty years of his life, art historians and his descendants believe that a friendship developed.33 Stuart was undoubtedly well acquainted with Russell Sturgis's brother-in-laws, James and Thomas Handasyd Perkins, who had both sat for him and were leading patrons of the arts in Boston. A page from Stuart's account book for April 1808 records an appointment for a sitting that appears to have been kept by "Mr. T. H. Perkins" and a note "to Mr. Perkins' to dinner" written two days later.34 In keeping with a friendship, the Sturgises were sympathetic to Stuart's concerns about unauthorized copies of his Washington portraits. In 1801 the Philadelphia merchant John E. Sword had imported one of Stuart's copies of his "Athenaeum" portrait of Washington into Canton with plans to make his own copies on glass, prompting a lawsuit by Stuart.35 George Washington Sturgis later imported one of Stuart's Washington portraits into Canton but was intent on reassuring the artist that it could not be convincingly copied. On October 19, 1822, he wrote to his father:

George Washington Sturgis's letter suggests that Stuart trusted the Sturgis family enough to risk allowing another Washington portrait to go to China. In the same letter, George Washington wrote to his father to thank him for the portrait of himself:

That George Washington was referring to his father's 1822 portrait by Stuart, which he brought home to Boston with him the following year, is evidenced by a very specific bequest recorded in the codicil of his will, written a couple months before his untimely death in 1826: "I do hereby give and bequeath to my daughter Anna Elizabeth the portrait of my Father Russell Sturgis painted by Stuart in 1822."38 Anna Elizabeth Sturgis died as a child in 1828, but the portrait more than likely remained with Russell Sturgis's widow during her lifetime.39 Copies were made of Stuart's final 1822 portrait of Sturgis, and in some cases the artist is identified. Sarah Goodridge (1788-1853), for instance, copied the portrait in miniature (about 1822, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). In 1926 the art historian Lawrence Park recorded three other copies of the portrait, including one by James Sullivan Lincoln (1811-1888) and another by a Miss Shepley. Park did not identify the artist of the third copy, but he listed the owner as Mrs. Frederick Parker, of Boston. The Worcester Art Museum's copy of Park's four-volume catalogue on Stuart contains dated notes signed by Alice Paine, who wrote across from Mrs. Parker's name, "now, 1962, owned by Mrs. Henry P. King, Marblehead, Mass."40 In 1980, the Sturgis portrait owned by Parker in 1926 and later by Mrs. Henry P. King was given by King to the Cape Ann Historical Museum in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and attributed to Stuart. The donor was the great-great-great granddaughter of the sitter.41 Although Park did not suggest that the artist of this third copy was Stuart, there is good reason to believe that two portraits by Stuart resulted from Sturgis's last sitting in 1822, and the Cape Ann portrait might be the second. In 1833 James Perkins Sturgis wrote from Canton to his sister Betsy:

James's request "for one of the last portraits which Stewart painted of our Father" suggests that the practically identical portrait of Russell Sturgis at the Cape Ann Historical Museum should be carefully considered. Notes 2. Sturgis 1914, 33. 3. The printer and bookseller John Boyle noted the marriage of Sturgis and Perkins in Boston in his diary on November 11, 1773: "Married, Mr. Russell Sturgis, to Miss Betsey Perkins, Dr. of the late Mrs. James Perkins." Boyle's Journal 1930, 368. For James Perkins see Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 19, 22. The second marriage of Russell Sturgis's younger brother Josiah Sturgis (1767-1835), a Charleston merchant, was to Esther Perkins, the younger sister of Russell's wife Elizabeth. See Sturgis 1914, 40. 4. Sturgis's signature appeared on a receipt for Thomas H. Peck on March 6, 1767, Caleb Davis Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Mass. See also Roberts II, 1897, 215. 5. Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 25-26. 6. Massachusetts Centinel (Boston), May 27 and June 3, 1789. For Samuel Sturgis, see Sturgis 1914, 39, and Lainhart 1986, 249. 7. The life dates of the children of Russell and Elizabeth Perkins Sturgis not mentioned in the text are James Perkins (1774-1790), Elizabeth Peck (1776-1776), Elizabeth Peck Peck (1777-1778), Thomas (1781-1782), Elizabeth Perkins (1783-1783), Charles (1784-1801), Sarah Paine (1786-1855), Elizabeth Perkins (1787-88), Ann Perkins (1795-1795), and Mary Perkins (1800-1801). Sturgis 1900, iv, and Sturgis 1914, 36-37. 8. Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 149-53, and Russell Sturgis, Boston, to Thomas H. Perkins, London, July 12, 1795, Thomas Handasyd Perkins Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, box 1, folder 1.4. 9. Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 156. 10. For Henry and George Washington Sturgis in China see Sturgis 1914, 37; Henry Sturgis, Macao, to George Washington Sturgis, Canton, April 2, 1819, and James Perkins Sturgis, Canton, to Henry Sturgis, Macao, April 8, 1819, Paine Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society (hereafter cited as PFP, AAS), Worcester, Mass., box 3, folder 1; George Washington Sturgis, Canton, to Ann "Nancy" Cushing Sturgis, Boston, January 9, 1810, PFP, AAS, box 2, folder 5; and George Washington Sturgis, New York, to Eliza Sturgis, Boston, May 14, 1823, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder 3. 11. For James Perkins Sturgis see Downs 1968, 426, 436; Downs 1997, 264, 364; James P. Sturgis, Macao, to Betsy Sturgis, Boston, March 22, 1851, 37, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder 5; Jacques Downs, email to Laura Mills, March 28, 2000, Worcester Art Museum curatorial files (hereafter cited as WAM files); and Tim Sturgis to Laura Mills, May 22, 2000, WAM files. For an explanation of the intertwined business and family relationships of the Boston China traders, including the Sturgis family, see Downs 1997, 367-69. 12. Russell Sturgis, Report of the Main Guard, August 10-September 6, 1773, William Heath Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, XI, 49, 71, 113, 179, 246. For more on Sturgis's commissions during the Revolution, see also Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors XV, 1906, 224. 13. Boston Town Records 1903, 224, 245, 277, 320, 350, 385, 418-19. 14. Ibid., 31, 305-6. 15. Roberts II, 1897, 215, and Massachusetts Legislative Biography Card File, State Library of Massachusetts, Boston. 16. Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 170. 17. Thomas Amory, Share in the School-House in Federal Street, November 4, 1797, Miscellaneous Bound, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 18. Alden 1955, 11, and Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 119-20. 19. Sturgis 1900, iv, and Frederic William Paine, London, to Mary L. Pickard, Rochester, May 6, 1826, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder 3. 20. Boston Commercial Gazette, September 11, 1826. Sturgis's death was briefly noted in the Columbian Centinel (Boston), September 9, 1826. 21. Roberts II, 1897, 215. 22. Will of Russell Sturgis, Suffolk County no. 28091. 23. Inventory of the estate of Elizabeth Perkins Sturgis, Suffolk County no. 33762. 24. Scholar Cuthbert Lee suggested that the fur in the 1822 portrait of Sturgis was an unusual accessory for Stuart, but that is not the case. Lee 1929, 40. 25. Both of these portraits descended in the family of Russell Sturgis's granddaughter Susan Parkman Sturgis Parkman (Mrs. John Parkman) (1810-1869), the daughter of his son, Nathaniel Russell Sturgis. They were acquired by the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester in 1942. Park 1926, II, 722, 724-25, cat. nos. 803, 806. 26. In 1879 this portrait was owned by Russell Sturgis (1805-1887), the grandson of the sitter through his son, Nathaniel Russell Sturgis. Mason 1879, 262. In 1926 the portrait was in the possession of Elizabeth Sturgis Grew Beal (Mrs. Boylston Adams Beal), who received it from her father, Henry Sturgis Grew, whose mother, Elizabeth Perkins Sturgis (Mrs. Henry Grew) (1809-1848), was the sister of the 1879 owner. In 1964 the portrait was owned by the daughter of Elizabeth Sturgis Grew Beal, Elizabeth Sturgis Hinds, of Manchester, Mass. Park 1926, 804, cat. no. 723; Mount 1964, 375; Sturgis 1925, 1, 4, 15, 45; Hill 1944; and Copley Society 1965, cat. no. 14. 27. According to the Smithsonian Art Inventories, National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C., pastel portraits of Russell Sturgis and Elizabeth Perkins Sturgis, attributed to a Sharples, were sold in lot 770 of the May 22-24, 1970, sale of Adam A. Weschler & Son of Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, their current location is unknown. 28. The Harding portrait is owned by descendants of the sitter. Lipton 1985, 182. 29. James Perkins Sturgis, Canton, to Betsy Sturgis, Boston, May 2, 1833, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder 4. 30. James wrote, "I hope to get the portrait of Mother before long, I requested you last year, to ask her to sit to Mr Newton, or other good artist for one; and doubt not that she has consented." James Perkins Sturgis, Canton, to Betsy Sturgis, Boston, January 13, 1834, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder 4. 31. Two portraits of James Perkins Sturgis in the possession of descendants are said to be by Chinnery. Tim Sturgis to Laura K. Mills, April 17, 2000, WAM files. Worcester's James Perkins Sturgis (1965.256) is not believed to be by Chinnery. Patrick Conner, Martyn Gregory, London, to Laura K. Mills, April 17, 2000, WAM files. In addition to the Peabody Essex portrait mentioned in the text, another James Perkins Sturgis in the same collection was attributed to Chinnery in Peabody Museum 1976, cat. no. 8, but it is no longer believed to be by the artist. Telephone conversation with Karina Corrigan, Asian Export Art, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., April 4, 2000. This portrait is very similar to Worcester's; the faces in both portraits are clearly of the sitter in the accepted Chinnery portrait at the Peabody Essex, but they are of a younger man. It is possible that the unidentified artist responsible for the Worcester and Peabody Essex portraits could be Chinnery's rival, the Chinese artist Lamqua, but the matter requires further study. Patrick Conner is credited with this suggestion. 32. Conner 1993, 165, and Perkins and Gavin 1980, 34. 33. For suggestions of a friendship between Sturgis and Stuart, see Sturgis n.d. [1893?], 59; Park 1926, 722; and Tim Sturgis to Laura K. Mills, May 22, 2000, WAM files. 34. Swan 1938, 308. Stuart portraits of James and Thomas Handasyd Perkins are in the collection of the Boston Athenaeum. T. H. Perkins patronized other American artists, including Washingon Allston, Horatio Greenough, Thomas Sully, and Alvan Fisher. In 1807 James Perkins had deeded his house on Pearl Street to the Athenaeum, and both T. H. and James Perkins contributed large sums to the Boston Athenaeum in 1823 to build an addition for an Academy of Fine Arts. T. H. Perkins remained active on the Athenaeum's fine arts committee. See Seaburg and Patterson 1971, 398-99, and Wentworth and Clark 1995, 48-52. 35. Richardson 1970, and Evans 1999, 86. 36. George Washington Sturgis, Canton, to Russell Sturgis, Boston, October 18-19, 1822, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder 3. 37. Ibid. 38. Codicil to the will of George Washington Sturgis, June 20, 1826, Suffolk County no. 28090. 39. Administration papers of Anna Elizabeth Sturgis, Suffolk County no. 28764. For a discussion of why Elizabeth Perkins Sturgis probably had the portrait after her granddaughter's death, see provenance. 40. The Goodridge miniature was a gift of Elizabeth Orne Paine Sturgis (d. 1911), the second wife of Henry Parkman Sturgis, in 1892. Henry Parkman Sturgis (1806-1869) was the grandson of the sitter through his son Nathaniel Russell Sturgis. In 1926 the Lincoln copy was in the possession of Russell Sturgis Paine, of Worcester, and the Shepley copy was owned by Frederick William Paine, of Brookline. Alice Paine's dated notes in the Worcester Art Museum's copy of Park indicate that in January 1964, Norman R. Sturgis owned the Lincoln copy. Park 1926, II, 724, cat. no. 805. 41. Mary Parker King (Mrs. Henry Parsons King) was the daughter of Mary McBurney Parker (1867-1889), who was the daughter of Susan Sturgis (1846-1923) and her first husband, Henry Horton McBurney. Susan was the daughter of James Sturgis (1822-1888), the son of Nathaniel Russell Sturgis, who was the son of Russell Sturgis. Sturgis 1925, 1, 6, 23, 55, 81. 42. James P. Sturgis, Canton, to Betsy Sturgis, Boston, June 16, 1833, PFP, AAS, box 3, folder |