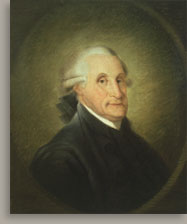

| Christian Gullager Born Copenhagen, Denmark, March 1, 1759. Died Philadelphia, November 12, 1826. Christian Gullager was a Danish-born artist who trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and by 1789 established himself in Boston as one of the "best portrait painters of this metropolis."1 Gullager worked in Newburyport in 1786, in Boston from 1789 to 1797, in New York City from the fall of 1797 to the spring of 1798, in Philadelphia from 1798 to 1805, and in New York again in 1806–07.2 Approximately sixty portraits are attributed to Gullager, many of which were painted in Massachusetts. He also painted scenery for the theater in Boston and New York, designed engravings and medals, and sculpted a bust of George Washington from life. Gullager even advertised himself as a miniaturist, although no surviving miniatures are assigned to him. The last twenty years of his life are undocumented, except for his return in 1826 to Philadelphia, where he died. Amandus Christian Gullager was born on March 1, 1759 to Christian Guldager Prang and Marie Elisabeth Dalberg of Copenhagen. His father was a servant to the government official Joachim Wasserschlebe (1709–1781), who was an avid print collector. Gullager studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen and received a silver medal there in January, 1803.3 Gullager would later claim that he had been "educated from his youth in the academy at Copenhagen."4 The only known portrait from his years in Denmark is Mrs. Bodel Saugaard Acke (location unknown), which is signed and dated 1782.5 The artist had emigrated to Massachusetts by May 9, 1786, the date on which he married Mary Maley Selman (1760–1835). She was the widow of Samuel Selman of Marbelhead, a port town about fifteen miles north of Boston. They were married by the Reverend John Murray (1742–1793) at the First Presbyterian Church of Newburyport, twenty miles north of Marblehead.6 The Gullagers had nine children, whose births Mary recorded on the back page of an account book and then transferred into the family Bible with marriage and death dates.7 Newburyport was a small but busy port and one of the wealthiest towns per capita in the state; it therefore attracted many artisans and skilled craftsmen. In 1786 Gullager was hired to paint the steeple of the Presbyterian church in Newburyport; in accepting that project, he was working in an eighteenth-century colonial tradition exemplified by Joseph Badger and Jeremiah Theüs of artisans who painted both buildings and portraits.8 His work on the North Shore also included at least five portraits of Newburyport sitters including Captain Offin Boardman and Sarah Greenleaf Boardman (Mrs. Offin Boardman) and Benjamin Greenleaf Boardman—and three of Gloucester sitters.9 The Boardman portraits have a pencil underdrawing and many changes, which are visible as pentimenti and suggest that he struggled in completing these early works. The neutral background, precise attention to costume details, large head and hands, and arms that do not appear to have a bone structure are features that are common to both Mrs. Boardman's portrait and Gullager's Danish portrait of Mrs. Acke. Gullager's style at this point in his career was typical of provincial Danish painting, rather than the academic style of the period.10 By 1789 Gullager was listed in the Boston city directory as a portrait painter in Hanover Street. His portrait Colonel John May (American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Mass.) indicates that he was in Boston by April 23, 1789, the date on which the sitter departed for Ohio. May's wife received the portrait the next day from her brother-in-law and wrote in her diary, "Much praise is due to the painter. He has done his work well."11 By the end of April Gullager had also completed a posthumous portrait of Elizabeth Sewall Salisbury (1789, Worcester Art Museum), who had died unexpectedly in March. Her husband Samuel Salisbury, a Boston merchant, wrote to his brother Stephen (also a merchant) in Worcester, "Mr. Gulliker has exceeded my expectation in the picture."{12 Samuel's recommendation resulted in a series of portrait commissions for Gullager in Worcester. Stephen ordered a replica of his sister-in-law's portrait (location unknown) and paid for Gullager to travel to Worcester, where the artist painted three more portraits between May 25 and June 13, 1789: Stephen Salisbury I, Martha Saunders Salisbury (Mrs. Nicholas Salisbury), and Elizabeth Salisbury Barrett (Mrs. Samuel Barrett) (Worcester Historical Museum). Martha was Stephen's mother and Elizabeth was his sister. Gullager continued to secure commissions through the Salisbury family network. In September 1789 he returned to Worcester at the request of Stephen's brother-in-law Daniel Waldo and painted two more portraits: Daniel Waldo and Rebecca Salisbury Waldo (Mrs. Daniel Waldo). During the same trip, he probably painted the portrait of another Worcester sitter, Dorothy Lynde Dix (location unknown).

During the same visit to Boston, Washington was also painted by Gullager's rival John Johnston (1751/2–1818). The Massachusetts Centinel declared Gullager and Johnson "the two best portrait painters of this metropolis" and "from laudable competition of such artists, we may expect elegance and accuracy."16 Early in 1790 Gullager sculpted a bust of Washington in plaster of Paris, and the local press once again celebrated his achievement: "The Connoisseurs who have visited Mr. GULLAGER'S room, to examine this beautiful piece of statuary, are unanimous in pronouncing its merits, and the merits of this ingenious artist who has produced it."17 In June Gullager was granted permission to display the bust permanently in Boston's Faneuil Hall, and by September the sculpture was on view and for sale in New York.18 It is possible that the bust on display in New York was a replica, since the artist's son later claimed that his father made multiples of it as well as portrait medals of Washington.19 While in Boston, Gullager also earned commissions for design work. He devised the seal of the Society for Propagating the Gospel Among the Indians and Others in North America (Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston).20 In 1790 Gullager drew an allegory of the four continents that Samuel Hill engraved for The Massachusetts Magazine. Gullager and Hill collaborated on another exotic subject that year, a frontispiece for Oubi; or the Virtues of Nature by the Boston writer Sarah Wentworth Morton (1759–1846).21 Gullager also made landscape drawings, as noted by Jeremy Belknap, "Went to Newton w[ith] Mr Elliot & Mr Gullager the latter took 2 perspective views—one of the fall from the point of Rocks below it. another of the House & other buildings from a Station ab[ou]t 4 Rods from the S W corner of the House within the fence."22 Gullager's interest in landscape subjects probably helped him to earn a position painting scenery for the Boston Federal Street Theatre. In November 1793 Gullager signed a contract to paint eight stage sets, including "one back Street scene. . .one inside Palace scene. . .one cultivated Garden scene. . .one drawing room scene. . .one Sea view & rock scene. . .and one front Street."23 According to the contract, all but the front street scene were to include wings. Gullager would be paid forty-five pounds per scene; the theater would supply the cloth and the artist would provide all other materials. Despite some difficulty meeting deadlines, Gullager continued to work for the theater until 1797.24

Gullager moved from Boston to New York in 1797. He is listed in the Boston city directory for 1796 as a "limner" on Tremont Street, and he was still receiving payment from the theater in Boston in May, 1797.26 By September he had moved to New York and began to advertise himself as a portrait and theatrical painter with a wide range of products: portraits in various sizes, "Decorations for Public and Private Buildings", "Frontispieces or Vignets" for publications, and "Paintings on Silk, for Military Standards or other ornamental purposes."27 Gullager also announced that he was planning to open a drawing academy, but New York already had an established art school operated by the Scottish emigrès Alexander Robertson (1765–1835) and Archibald Robertson (1772–1841).28 Since Gullager's subsequent advertisements do not mention the academy, it appears that he failed to realize that plan.29 By May 1798 Gullager had moved to Philadelphia, where he promoted his "Portrait and Ornamental Painting Rooms." His studio was located at Fourth and Chestnut Streets, just one block east of Charles Willson Peale's museum of art and natural history.30 Gullager targeted his decorative painting at the militia companies and other civic organizations that might need painted flags, drums, and fire buckets, for instance. Gullager's advertisements claimed that his work was superior to that of his principal competitor, George Rutter and Company, "for elegance of design, truth and beauty of colouring, [and] neatness and masterly execution."31 A receipt for forty dollars and an extant standard for the First City Troop of Philadelphia (1798, First Philadelphia City Cavalry) hint that Gullager achieved a degree of success there.32

Between 1803 and 1805 Gullager presented himself as a miniature painter, although no surviving miniatures have been assigned to him. By 1806 Gullager left Philadelphia and was seeking employment as a theater painter in New York.33 Although the artist was still alive, his wife appeared in the city directory that year as "Gullager widow of Christian." With help from fellow artist William Dunlap, Gullager was hired in 1807 by Thomas Cooper to paint scenery for the theater in New York. According to Dunlap, however, Gullager was soon fired for his inability to complete the set in a timely fashion.34 This episode is the last that is known of his career. Gullager's indolence apparently contributed to family troubles as well, and in 1809 his wife was granted a divorce by the Common Pleas Court of Philadelphia County.35 Mary Gullager stayed in Philadelphia, where she earned her living as a shopkeeper and by 1822 was retired as a "gentlewoman." The artist's whereabouts between 1807 and 1826 remain unknown. Shortly before his death, he reappeared in Philadelphia and died at the home of his granddaughter Elizabeth Adams Ball.36 Notes 2. The most thorough studies of Gullager to date are Dresser 1949b and Sadik 1976. 3. Sadik 1976, 11–12. 4. The Minerva and Mercantile Evening Advertiser, New York, September 18, 1797. 5. Sadik 1976, 47–49. 6. For Mary Maley's birth, see Marbelehead Vital Records 1903, I, 332. For her first marriage, see Newburyport Vital Records 1911, II, 426. For the marriage of Christian Gullager to Mary Maley Selman, see Newburyport Vital Records 1911, II, 204 and Gulager 1934, n.p. 7. Mary Gullager's account book is in the Gulager Family Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP), Philadelphia; the Gullager family Bibles are also at HSP. The Gullagers' children were Caroline (1787–1856), William Maley (1788–1848), Christian (1789–1863), Mary Maley (1790–1879), Andrew (b. 1793), Charles (1794–1840), Henry (1795–1863), Benjamin Maley (1798–1810), and Eliza (b. and d. 1800). 8. James M. Barriskill, Old South Presbyterian Church, Newburyport, to Louisa Dresser, Worcester Art Museum, September 21, 1954. 9. Gullager's Gloucester portraits include David Plumer and Mary Sargent Plumer (Mrs. David Plumer) (both 1787, Sargent House Museum, Gloucester, Mass.) and Reverend Eli Forbes (about 1786–87, Cogwell's Grant, Essex, Mass., Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities). 10. Sadik 1976, 48. 11. Abigail May, Diary, April 24, 1789, as quoted in Edes 1876, 46. 12. Samuel Salisbury, Boston, to Stephen Salisbury, Worcester, April 29, 1789, Salisbury Family Papers, American Antiquarian Society, hereafter cited as SFP, AAS, Worcester, box 5, folder 6. 13. The preliminary sketch and a replica of the portrait remain unlocated. Dresser 1949b, 164. 14. Jeremy Belknap, Diary, October 27, 1789, Jeremy Belknap Papers, Belknap Diaries, 1786–1789, Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS), Boston. 15. George Washington, Diary, November 3, 1789, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, as quoted in Dresser 1949b, 164. 16. Massachusetts Centinel, Boston, November 14, 1789. 17. Massachusetts Centinel, Boston, March 27, 1790. The bust was also noted in William Bentley, Diary, April 5, 1790, Bentley diary 1962, I, 58. 18. Boston Selectman's Minutes 1896, 124; Gazette of the United States, New York, September 1, 1790. 19. No bust or medal of Washington by Gullager has been located. Charles Gulager to Henry Gulager, March 5, 1832, quoted in Gulager 1934, n.p. For a discussion of Gullager's bust of Washington, see Sadik 1976, 35–44. 20. Sadik 1976, 42. 21. Dresser 1949b, 176–79. 22. Jeremy Belknap, Diary, November 20, 1789, Belknap Papers, Diaries, MHS. 23. Contract between the Trustees of the Boston Theatre and Christian Gullager, November 9, 1793, Boston Theatre (Federal Street) Papers, Dept. of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department. Courtesy of the Trustees, Ms. Th.1 C2. 24. For Gullager's tardiness in completing the theater scenes, see Minutes of the Trustees, February 21, 1795, Boston Theatre (Federal Street) Papers, Dept. of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department. Courtesy of the Trustees, Ms. Th.1.P48, v. 1. See also, Alden 1955, 17, 18. 25. Columbian Centinel, Boston, November 16, 1791. 26. John Williamson to Christian Gullager, May 1, 1797, Boston Theatre (Federal Street) Papers, Dept. of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Boston Public Library/Rare Books Department. Courtesy of the Trustees, Ms. Th.1.T11B (56). 27. The Minerva and Mercantile Evening Advertiser, New York, September 18, 1797. Gullager also placed the advertisement in the Commercial Advertiser, New York, October 2 and 11, 1797. 28. For the Columbian Academy, see Commercial Advertiser, New York, October 11, 1797. 29. See, for example, The Time Piece, New York, October 13 to November 17, 1797, quoted in Kelby 1922, 40–41. 30. Gullager would later appear in the city directory for 1798 at 50 North Front Street; in 1800 at 33 North Front Street; in the Philadelphia New Trade Directory for 1800 at 45 Callowhill Street; in 1801 at 93 North Front Street; and in 1805 at 70 Mulberry Street. 31. Gullager's advertisement was printed in the Gazette of the United States, and Philadelphia Daily Advertiser, May 5, 1798; Rutter's very similar ad appeared in the same newspaper, May 3, 1798. The two ads were published together May 8, 1798. 32. Scharf and Westcott 1884, II, 1045–46; Wilson 1915, 247; and Sadik 1976, 28–29. 33. Dunlap diary 1931, II, 407–08. 34. Dunlap 1918, II, 284–85. 35. Gullager vs. Gullager, Common Pleas Court, Philadelphia County, transcript in Christopher Floyd Gulager family folder, HSP. 36. For Gullager's death, see Gulager 1934, n.p. For his burial at the Second Presbyterian Church Yard, Third and Arch Streets, see Second Presbyterian 1898, II, 474. |