Joseph Blackburn

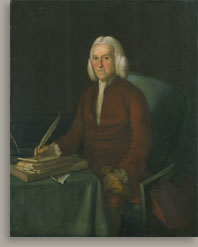

Joseph BlackburnHugh Jones, 1777

Description

Hugh Jones is a three-quarter-length portrait. The seated figure is turned three-quarters left, with his blue eyes looking toward the viewer. He is an alert elderly man wearing a white wig, which is parted in the middle. The face is modeled in blended yellows, reds, and grays, and the cheeks are painted in a rosy pink over peach flesh tones.

The sitter wears a reddish-brown coat and breeches, apparently made of wool. The collarless coat is adorned simply with cloth-covered buttons, the top three of which are unfastened. The proper right cuff is folded back and secured by two more buttons. A plain white neck cloth is tied at the neck and secured near the fringed ends with a band. The ruffled white cuffs of the shirtsleeves are visible on each hand. A brass buckle secures the cuff of the breeches.

The figure is seated in a green upholstered chair with a low, gently arching back. The upper portion of the chair frame, including the arms, is painted the same green as the upholstery. Below the seat, the frame and legs of the chair are dark brown. The sitter is working at a table draped with a green cloth.

With his proper left hand, the man holds against his thigh a yellow bag, which is gathered at the top. The forward edge of the bag and the knuckles are highlighted. In his proper right hand he holds a quill pen, the point of which rests on the top sheet of paper in a stack of documents. The front edge of the sheet curls up slightly to reveal a manuscript note that is only partially visible but appears to include the tops of characters spelling out a date, perhaps "Oct[ober] 10 [or 18 or 19]." Although partially obscured, the letters on the next document in the stack appear to spell "Charles Morgan Es." A red ribbon binds together the next eight documents. Below these papers is a volume of lavender-edged pages bound with a yellow-brown cover and inscribed, on the spine, "Abstracts of Ruperra/Rentalls/From ye year/1725 to Octob/24th—1777." The bottom sheet of paper on the table is partly tucked under the volume; its front corner hangs over the edge of the table, and its left corner turns up sharply, creating a deep shadow in the fold. This trompe l’oeil element is inscribed with the artist’s signature and the date 1777. Behind and to the left of these objects is a gray inkwell, probably pewter, holding a second quill that continues beyond the edge of the canvas. The background is dark brown. Level with the man’s chest there are two ridges that appear to define the upper molding of wainscoting.

Biography

The sitter was incorrectly identified in 1962 as Dr. Charles Gould, confusion apparently arising from the exchange of frames between this and another portrait.1 Charles Gould was the name of one of the heads of the Morgan family. Sir Charles Gould (1726–1806) married Jane Morgan in 1758, and when she inherited the estate in 1792, he took the name Morgan by Royal License.2 It is not clear whether Dr. Charles Gould is the same man or a namesake. In either case, a manuscript label apparently written in 1783 and affixed to the back of the canvas correctly identifies the sitter as Hugh Jones, who was born about 1698 and died in October 1777.3

|

|

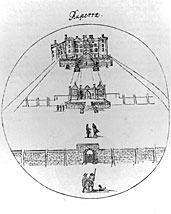

| Figure 1. Thomas Dineley, Ruperra, sketch drawn August 18, 1684, in Thomas Dineley, The Account of the Official Progress of His Grace the First Duke of Beaufort through Wales in 1684 (London: Blades, East & Blades, 1888), 358. A view of Ruperra Castle, South Glamorgan, Monmouthshire, Wales, built 1626, restored 1783-[17]89. Photography courtesy of Newport Library & Information Service, Newport, South Wales. |

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Tredeagar, aquatint, in James Baker, A Picturesque Guide to the Local Beauties of Wales, 1791. A view of Tredegar House, Newport, Monmouthshire, Wales, built fifteenth century, expanded seventeenth century. Photography courtesy of The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, Dyfed. |

Tredegar was decorated not only with portraits of Morgan family members but also with scenes from the Bible and classical mythology. By the late seventeenth century the family employed at least forty-six servants at the house, with the agent—Hugh Jones’s position—at the top of the pay scale. When the house was sold in the 1950s, it first became a boarding school and then a public school. The Newport Borough Council acquired the property in 1974 and restored it as a national landmark.7

Analysis

Hugh Jones was one of at least sixteen portraits Joseph Blackburn painted between 1764 and 1777 in Wales, southwestern England, and Dublin. They include Thomas Hughes and Elizabeth Hughes (both 1774, Art Gallery and Museum, Cheltenham). Thomas Hughes’s father and grandfather had been agents to the Morgans at Tredegar, the same position Hugh Jones later held. Blackburn also painted Morgan Graves (1708–1770), the son of Elizabeth Morgan, in Herefordshire in 1768.8 Those connections are tantalizing, because they hint at a patronage network similar to the one through which Blackburn earned commissions in the American colonies—a network based on letters of introduction and the cultivation of familial and social connections.

After painting in Bermuda and New England between 1752 and 1763, Blackburn returned to England, where he presumably had trained at the beginning of his career. Hugh Jones is his last known signed and dated portrait and demonstrates considerable continuity in style and composition with his American likenesses. The three-quarter-length view and standard size (fifty-by-forty-inch canvas) are typical of his most common format. Blackburn’s signature facility with costume, especially in the gentle folds of cloth created by the tension of a fastened coat on a seated body, is evident even in this sitter’s plain garb.9 The painting also recalls Blackburn’s American portraits in its convincing depiction of a stack of papers and in the trompe l’oeil effects of a sheet of paper hanging over the edge of the table. Notably, the most conspicuous of these sheets bears the artist’s signature and the year he painted the portrait.

The book in the portrait is inscribed to show the span of Jones’s service—1725 to 1777—to the Morgans. Tredegar House manuscripts in the National Library of Wales include a volume of accounts kept by Jones and his successor between 1771 and 1778; that book supports Jones’s death date of 1777, since his signature appears among the entries for 1777 but not the part of the volume for 1778.10 Because the book in the portrait concludes on October 24, 1777, and a label on the back of the canvas gives Jones’s death year as 1777, it is possible that he actually died on October 24. In that case, the painting may be a posthumous portrait or one that was at least completed after the sitter’s death. Jones’s professional importance depended upon the fact that the rentals derived from 40,000 acres of agricultural land in Monmouth, Brecon, and Glamorgan counties were a principal source of income to the Morgan family.11 Later inventories of paintings hanging at Tredegar House suggest that Jones was the only non-family member to have his portrait painted.

Throughout his career, Blackburn depicted men of affairs seated at worktables, quill in hand or nearby, and surrounded by letters, documents, or ledgers. In 1752 he thus portrayed Francis Jones (1698–1776) (portrait owned by James Maroney, New York, as of 1980) commander-in-chief and vice-admiral of Bermuda Island and president of the Council.12 In that work, the sitter, gesturing toward an open window, holds a letter in his lap; there are several others on a table beside an inkwell. Blackburn’s Newport, Rhode Island, portrait John Brown (1754, John Nicholas Brown Center, Brown University, Providence) shows a gentleman with quill in hand, composing a letter.13 Another folded piece of paper extends over the front edge of the table and an inkwell holds a spare pen, as in Hugh Jones. Brown’s posture is erect, his legs are crossed, and his left hand is tucked into his waistcoat—all signs of his gentility. Blackburn’s Portsmouth, New Hampshire, portraits Colonel Theodore Atkinson and Samuel Cutts (1762–63, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) are also variations on this theme.14 Although the artist depended upon stock motifs to represent these men of affairs, he varied their poses and personalized their features, bodies, clothes, and stature. Clearly proud of his ability to render convincing still lifes, including folded paper and the textures of feathers, pewter, and textiles, he also tailored these elements to his sitters: Colonel Atkinson’s portrait features the provincial seal of New Hampshire, and Hugh Jones’s alludes to the subject’s employer and his fifty years of service in the Morgan household. In terms of style, the portrait of Cutts differs in its exaggeratedly strong modeling. Those of Jones and Atkinson are characteristic of the subtler modeling that Blackburn introduced to his portraits in the late 1750s, whereas the features of his earlier figures are simplified and stylized, as in Isaac Winslow and His Family (1755, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Similar compositions were common among eighteenth-century British and American painters. For instance, Thomas Hudson, who possibly was Blackburn’s teacher, painted the composer George Frideric Handel (1747, National Portrait Gallery, London), seated with papers and musical compositions at his side.15 John Smibert (1688–1751), the Scottish-born, London-trained follower of the Lely-Kneller school, painted Henry Ferne in 1730 (Worcester Art Museum) in a similar manner. That portrait was completed in London before Smibert moved to Boston, where he was the leading portraitist until his health began failing in the mid-1740s. The American limner Joseph Badger also employed the convention of a businessman at work in his portrait Cornelius Waldo (1750), which derived in large part from an imported English engraving of Sir Isaac Newton by John Faber, Jr. (after John Vanderbank). Copley, too, interpreted this theme in such portraits as John Hancock (1765, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Thomas Boylston II (1767, Harvard University Portrait Collection, Cambridge, Massachusetts), and Robert Hooper (1767, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia).

The Worcester Art Museum acquired Hugh Jones as part of an effort to place American artists in a transatlantic, Anglo-American context, a connection already demonstrated in works painted by Ralph Earl in England and America and John Smibert in England and America (the American Smibert proved to be a fake) and in a tray painted by Robert Salmon. The Blackburn painting was also valued because it exemplifies characteristics considered desirable in early American painting: a forthright style rather than an overblown Grand Manner court style, a convincing still life, and a humble sitter rather than an aristocrat.16

Notes

1. Steegman II, 1962, 165; Dresser 1966a, 49.

2. Burke and Burke 1956, 2171; Freeman 1989, 8.

3. This is based on the manuscript label on the back of the canvas, which notes that Jones died in 1777 at about age seventy-nine.

4. Freeman 1989, 7.

5. Worsley 1986, 1277–79.

6. Chambers 1728, I, n.p.

7. James 1977, n.p.

8. Information on portraits painted by Blackburn in Wales is from clippings in the files of the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, provided in Jonathan Vickers to Laura K. Mills, May 15, 1998.

9. Richard Saunders proposed that Blackburn probably worked in London early in his career as a drapery painter, in Saunders and Miles 1987, 193.

10. Tipping 1908. A 1933 inventory of Tredegar House lists "J. BLACKBURN. Portrait of a Gentleman in red dress and white wig, seated at a table, writing. S. & D. 1777. 49 x 39 ins." Reported in a letter from M. Adcock, Tredegar House and Park, Newport, South Wales, to Laura K. Mills, May 20, 1998. For the environment in which Jones was employed and the portrait was originally displayed, see Apted 1972–73, 125–54; Haslam 1978, 994–97; Worsley 1986; and Freeman 1989.

11. Paul Joyner, assistant curator, National Library of Wales, to Laura K. Mills, June 24, 1998.

12. Morgan and Foote 1937, 21–22 and opposite; advertisement, The Magazine Antiques 118, no. 6 (December 1980): 1087.

13. Stevens 1967, 99–100.

14. Caldwell and Roque 1994, 33, 35–36.

15. The observation that Blackburn’s work reflects the influence of Thomas Hudson or Joseph Highmore was first made in Park 1919a, 75–78. Park shortly thereafter asserted that "Hudson may have been his master." (1923a, 8). For the portrait of Handel, see Miles and Simon 1979, cat. no. 34, n.p. Such portraits are also closely related to the long tradition of scholar portraits, in which the papers are letters, scientific treatises, maps, and other indications of scholarship. That tradition was recently examined in Fortune and Warner 1999.

16. Memorandum, Louisa Dresser to Daniel Catton Rich, Director, April 16, 1962, object file, Worcester Art Museum.