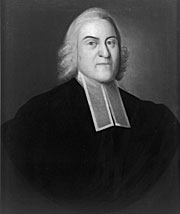

| Joseph Badger Born Charlestown, Mass., March 14, 1707/8. Died Boston, May 11, 1765. Joseph Badger began his career as a house painter-glazier and expanded his business to include portraiture. He was a Boston artist who made portraits of subjects in such nearby towns as Brookline, Charlestown, and Milton. How he learned to paint remains a matter of speculation, although several art historians have suggested John Smibert as an early influence and John Singleton Copley as a late one. Badger’s consistent use of an underpainting supports the theory that he received some training; those same cool, preliminary tones are now visible through abraded paint layers and have led some commentators to pronounce his subjects "wraithlike." At least 150 portraits are either extant or known to have been executed between 1743 and 1765. Badger has been described as a folk painter and an artisan painter, designations that suggest both his limitations as an artist and his natural abilities. His small repertoire of poses and formats facilitated the identification of his uniformly unsigned canvases. Like other eighteenth-century American painters, ranging from anonymous overmantel artists to the fashionable Copley, Joseph Badger depended upon imported English prints as sources for his compositions. More than one-third of his surviving paintings depict children, who are often represented with a pet bird, squirrel, or dog or, in the case of toddlers, holding a rattle. His portraits were created in a distinctive linear style, often with awkward proportions and little modeling. Despite these limitations, Badger was able to achieve specific likenesses of his sitters.1 Badger was born on March 14, 1707/8 in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the sixth of nine children of Mercy Kettell and Stephen Badger, a tailor. On June 2, 1731, Joseph married Katharine Felch in Cambridge, and the couple had between six and nine children.2 At least two of the Badgers’ sons, Joseph and William, became painters and glaziers like their father. (Moving to Charleston, South Carolina, shortly after their father’s death in 1765, the brothers announced that they had "just arrived from Boston, in New-England, and propose to carry on their business of painting and glazing in all their branches.")3 Another artist in the Badger family was Daniel, perhaps one of Joseph’s brothers, who moved to Charleston about 1735 and advertised that he "undertakes and compleats all sorts of House and Ship paintings."4 The young Badger family moved to Boston about 1733, settling in the neighborhood of Brattle Street and attending the Brattle Square Church, where four of Joseph and Katharine’s children were baptized. Joseph’s patrons included the colleague pastor of the church, the Reverend William Cooper (about 1743, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston) and a number of parishioners, including John Larrabee.5 The Brattle Street (now Franklin Street) neighborhood was home to several painters and other artisans, including John Singleton Copley, John Greenwood, Peter Pelham, and John Smibert. The Scottish-born Smibert (1688–1751) emigrated from London in 1728 and introduced the baroque Lely-Kneller portrait tradition to the northern colonies. He established a studio in Boston on Queen Street (now Court Street), a block from the church where the Badger children were baptized. Smibert also ran a shop that would have given Badger access to "all Sorts of Colours, dry or ground, with Oils and Brushes, Fans of several Sorts, the best Mezzotinto. Italian, French, Dutch and English Prints, in Frames and Glasses, or without, by Wholesale or Retail at reasonable Rates."6 Whether Badger received instruction from Smibert cannot be determined, although his work does reflect knowledge of the British artist’s paintings. Smibert’s shop also may have provided the English prints that served as sources for Badger’s portraits. The importance of prints to Badger’s development as an artist is widely evident. For instance, Thomas Cushing (about 1745, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts) and Cornelius (1750) and Faith Waldo (about 1750) are alike depicted in high-backed chairs in poses borrowed from an English mezzotint of Sir Isaac Newton by John Faber (1725, after John Vanderbank). Smibert, too, used this print as a source for his portrait of Daniel Oliver (1732, private collection).7 Smibert’s failing eyesight and health in the mid-1740s and his death in 1751 left a gap in the Boston portrait market that Badger filled until the arrival of Joseph Blackburn in 1755 and the emergence of Copley as an artistic force shortly thereafter. Badger continued to paint during the last decade of his life. Also in the Brattle Street neighborhood was Thomas Johnston (1708–1767), a versatile artist who painted portraits and coats of arms; japanned and painted furniture; engraved maps, music, bookplates, and clock faces; and cut gravestones. Johnston lived on Ann Street, east of Brattle Square.8 He trained John Greenwood (1727–1792), who was his apprentice from 1741 to 1745. Johnston was active in the Brattle Square Church, so it is very likely that the two knew each other. Like Smibert, Johnston sold artists’ materials. Indeed, the extant account books of Daniel Rea I, later Johnston’s business partner, identify Badger as a customer in 1751 and 1752. He was credited for a picture and for decorating buckets, items that were then probably resold to a third party, and he was charged for a hat and sundries.9

Badger’s vocation of painter-glazier combined two related building trades. According to The Builder’s Dictionary, published in London in 1734, "Glazing is a manual Art, whereby the Pieces of Glass (by the Means of Lead) are so fitted and compacted together by straight or curved Lines, that it serves as well for the intended Use, (in a manner,) as if it were one entire Piece; nay, in some Respects far better and cheaper, viz. In case of breaking, &c."12 The same source states that the most capable glaziers made drawings in preparation for their windows, indicating that an apprentice in this trade would have received at least rudimentary technical-drawing lessons. It is not known how Badger learned to be a glazier, but an apprenticeship seems likely. A painter is defined in The Builder’s Dictionary as one who paints pictures as well as the insides and outsides of buildings. Badger’s work in these trades is demonstrated by his trip in 1737 to Dedham to paint a house and, in 1738, by his petition to the Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas to attach the goods of Nathaniel Ames for nonpayment for painting window frames.13 Exactly when Badger expanded his business to include portrait painting is unknown, but the earliest proposed date, about 1743, is for Rev. William Cooper (Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston).14 Badger is described in 1756 as a "Limbner" and the following year as a "Faice painter."15 He continued in these and related activities throughout his life, and he is listed as "glazier" and "painter" in the probate papers filed after his death.16 His newspaper obituary recognized Badger as a "limner," suggesting that he was known publicly as a portraitist.17 None of Badger’s portraits is signed, and attributions and dates are based on the relative consistency of his style compared to a small group of documented portraits. A handful of paintings include inscriptions that can be related to other evidence to establish a clear date. The earliest example for which a firm date can be established is Portrait of John Gerry (Bayou Bend Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston), which is inscribed on the front, "AE 3Ys 8 M.," placing the commission clearly in 1745.18 James Bowdoin (about 1746–47; two versions, Bowdoin College Art Museum, Brunswick, Maine, and Detroit Institute of Arts) is also documented with a payment to the artist at the time of the subject’s death in 1747.19 The portrait of Cornelius Waldo is dated 1750 on a document at the sitter’s worktable and on a second date inscription that probably was added later. Other portraits bear date inscriptions that are thought to have been added later to the front and back of canvases and to stretchers and frames. The Orne family portraits have long stood as a benchmark, because the family account books clearly identify the artist as Badger and the time of the commission as 1756–57. Badger’s customers, who were similar to those of other colonial portraitists, included clergymen, merchants, and public officials. He also painted a few fellow artisans, including a baker, George Bray (1762, destroyed); a shoemaker, William Scott, (about 1764, location unknown); and a pewter maker, John Carnes (about 1755, location unknown).20 Although no self-portraits are known, he depicted several members of his own family, including his son (or grandson) Benjamin (about 1762, Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware), grandson James (about 1762, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and four members of his nephew Jonathan Badger’s family.21 He received commissions to paint individual portraits of entire families, including the Fosters of Charlestown (five portraits, 1755: four at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and one unlocated), the Ornes of Salem (six portraits, 1757–58: two at the Worcester Art Museum; two sold at Sotheby’s; and two unlocated), and the Brays of Boston (five portraits, 1762, destroyed). Only one double likeness by Badger is known, Portrait of Two Children (about 1760, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Williamsburg, Virginia), and in that work he made no attempt to integrate the figures into a unified composition. In addition, Badger received occasional posthumous commissions, including one for Elizabeth Royall (1747, New England Historical and Genealogical Society, Boston), which represents the woman’s recumbent corpse behind curtains.22 Badger’s prices for portraits may be determined clearly in at least two instances. Timothy Orne recorded the price of his and his wife’s portraits at six pounds each and of the four children’s portraits at a total of five pounds, five shillings. Orne also recorded the purchase of "a Painted Highlander" and "a Painted Laughing Boy" for fifteen shillings apiece.23 The art historian Richard Nylander proposes that these were hand-colored mezzotints.24 The price of the five Bray family portraits is fixed in court records for 1762 at eight dollars each, since Badger had to file a plea to attach his customer’s goods for nonpayment.25 By comparison, John Smibert was charging twelve guineas, more than double what Badger received for the portraits of Timothy and Rebecca Orne.26 Despite his success in earning commissions for at least 150 portraits, Badger died in 1765 with more debts than assets. He had purchased a house on Temple Street from William Story in 1763 for fifty pounds.27 The property was valued at 120 pounds in Badger’s probate inventory, and his entire estate totaled more than 140 pounds. Evidence of his work as a painter is hinted by just a few possessions: "pots, brushes, Stones &c," valued at twenty shillings, "a Coat of Arms," six shillings, and "a Chaise Body & Carriage," four pounds.28 Claims against Badger’s estate totaled nearly 179 pounds.29 Three years later, his widow, Katharine, settled the estate by selling their three-room house.30 Notes 2. The Badger-Felch marriage is noted in Baldwin, 2, 1915, 21. According to the Badger genealogy, Katharine Felch (born 1693) was the daughter of Deacon Francis and Ruth Smith of Reading, Massachusetts, and the widow of Samuel Felch. Badger 1909, 11. However, Lawrence Park provides the more likely identification of Mrs. Badger as Katharine Felch (born 1715), the daughter of Samuel and Katharine Smith Felch. Park 1918a, 4. The elder Katharine Felch had five surviving children at the time of Samuel Felch’s death, which would have been a great financial burden to the struggling artisan Badger. Paige 1877, 542. The Badger genealogy lists eight children born to the couple: Joseph (baptized 1731/32 and died young), Samuel (baptized 1734), Joseph, Jr. (baptized 1736), Daniel (baptized 1738), William (baptized 1742), Elizabeth (baptized 1745), Benjamin (died 1835), and perhaps Hannah (died 1841). Badger 1909, 11. Park adds a daughter, Katharine (born about 1739), whose birth record has not been found but whose marriage intentions were published in 1758. Park omits Benjamin and Hannah, either unaware of them or having dismissed them as members of the next generation of Badgers. Park 1918a, 4. Park names five children, the family genealogy eight, and Nylander eight or nine. Nylander 1972, 8. The birth dates of the Badgers’ children argue further against a marriage to the elder Katharine Felch, since she would have been about fifty-two years old at the time of Elizabeth’s birth. Baptisms are noted in Brattle Square 1902, 156, 159, 165, 169. 3. South-Carolina Gazette, Charleston, December 8, 1766, as quoted in Cohen 1953, 56. 4. South-Carolina Gazette, Charleston, December 6, 1735, as quoted in Prime 1929, 1, 299. 5. Park 1918a, 12; Brattle Square 1902, 131, 133, 136. 6. Weekly Rehearsal, Boston, October 14, 21, and 28, 1734. 7. Sellers 1957, 424–27. 8. Lyman 1955, 67. 9. Daniel Rea Account Books, v. 2, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetts. For debit entries to Joseph Badger, see March 18, 1751, and June 15, 1752, and for credits, see June 26, 1752. See also Swan 1943, 212. 10. Prown 1966, 1, 9–14. 11. Ibid., 1, 14 n 9. 12. Builder’s Dictionary 1734, 1, n.p. 13. Park 1918a, 5; Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas, Boston, August 4, 1738, vol. 210, 25032; and vol. 313, 47702. 14. Park 1918a, 12. 15. Memorandum books, 1756 and 1757, Timothy Orne Business Papers, box 16, folder 5, Philips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., as quoted in Dresser 1972, 1. 16. Suffolk County Registry of Probate, Boston, docket 13862. 17. Boston Gazette and Country Journal, May 13, 1765. 18. Warren 1998, 168. 19. Goodwin 1886, 17. 20. Park 1918a, 10, 11. For William Scott’s portrait, see New-Hampshire Gazette, and Historical Chronicle, Portsmouth, February 3, 1764. 21. Warren 1980, 1043–47. 22. Miles 1995, 2–10; Rumford 1981, 42, 43–44; Lloyd 1980, 110. 23. Dresser 1972, 1 24. Nylander 1972, 24. 25. Suffolk County Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Boston, vol. 84809, 498. 26. Smibert 1969, 16. 27. William Story to Joseph Badger, deed, May 9, 1763, Suffolk County Registry of Deeds, Boston, vol. 99, 273. 28. Inventory of the estate of Joseph Badger, Suffolk County Registry of Probate, Boston, docket 13682, vol. 64, p. 532. 29. Claims of creditors to the estate of Joseph Badger, August 8, 1766, Suffolk County Registry of Probate, Boston, docket 13682, vol. 64, p. 532. 30. Katharine Badger to Samuel Jepson, Suffolk County Registry of Deeds, Boston, August 30, 1768, vol. 113, 88. |